Like many other Indian companies, the Tata group too has globalised in the past decade. It is a testimony to the success of Indian enterprise in the global marketplace that many of them have done well, in the face of severe competition.

Barring a four-year interlude in the 1930s, a Tata scion has always headed the 141-year-old Tata group of companies.

Barring a four-year interlude in the 1930s, a Tata scion has always headed the 141-year-old Tata group of companies.

So Ratan Tata's statement that a non-family professional, even an expatriate, can succeed him has understandably become headline-grabbing news.

This is, however, not the first time an Indian business leader is casting his net globally in search of a successor, nor indeed, is it the first time for a Tata company.

The group's hotel business is, in fact, headed by an expatriate. However, the idea of an expatriate heading one of India's iconic business empires would naturally make waves.

The Tata name is inextricably linked with India's national movement and emergence as an independent nation.

Thus Ratan Tata's decision to look beyond national borders for a successor is imbued with all manner of symbolism.

Nothing is, however, more relevant to the symbolism of the decision than the fact that Mr Tata himself mentioned that 65 per cent of the group's revenues now come from its global business.

Like many other Indian companies, the Tata group too has globalised in the past decade. It is a testimony to the success of Indian enterprise in the global marketplace that many of them have done well, in the face of severe competition.

If the Tata group has to continue to hold its head high globally, it needs world class leadership with global experience. Mr Tata's decision should, therefore, reassure his shareholders.

It is, of course, entirely possible that even after he casts his net globally, Mr Tata may end up hiring an Indian national!

After all, many Indian nationals and people of Indian origin do head global businesses today. Indira Nooyi at Pepsi is just one very obvious name that would come to anyone's mind. Indian professionals have tested their mettle and proved their worth in highly competitive global organisations and markets.

They combine Indian values with global skills. So, Mr Tata has a wide pool of talent to choose his successor from. On a less ebullient note, one must also recognise that Mr Tata's decision may well have been shaped by his own experience in going global.

In 2007, Tata Steel paid $13 billion to buy Anglo-Dutch steelmaker Corus, and in 2008 Tata Motors paid $2.3 billion to acquire Jaguar Land Rover.

While both the Corus and the JLR decisions were thought through, they have also been huge learning experiences for the group and for Mr Tata himself. Tata Steel's global foray has been a mixed blessing for the group. It remains to be seen how wise the JLR decision will yet turn out to be.

As Mr Tata himself stated, these decisions have brought growth but also exposed the group to turbulence in global markets.

In sailing through potentially choppy waters, a captain with experience of manning bigger ships in wider oceans can always reassure shareholders and stakeholders.

That could well be one of Mr Tata's objectives, apart from the fact that there is no obvious successor waiting to fill his big shoes.

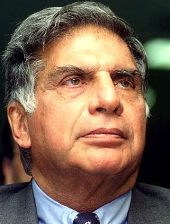

Image: Ratan Tata