All aircraft engines need to be put through rigorous tests before they are sold. What will happen in case of a bird hit, or if a fan blade disengages? Done physically, each of these tests can cost up to $15 million.

And each test has to be carried out under different conditions. This can burn hundreds of millions of dollars.

General Electric, the world's leading maker of aircraft engines, carries out all such tests on computers in an industrial estate in Bangalore at a fraction of the cost and time.

As a result, GE hopes to roll out four or five new engines over the next five years. An engine can take up to 20 years to develop. Nobody has ever flooded the market with so many engines in a span of just five years.

Ever since it was inaugurated in September 2000, the John F Welch Technology Centre has helped GE cut drastically go-to-market time (up to 50 per cent in some cases), save huge amounts of money and develop products for world markets.

Spread over 50 acres, dotted with gulmohar, cypress and palm trees, the centre employs over 3,800 scientists and engineers -- 13 per cent of them women. Every sixth GE technologist is in Bangalore (and its two arms in Hyderabad and Mumbai).

By 2010, every fourth GE technologist will operate out of here. It has filed for over 850 patents so far. It is GE's largest technology centre anywhere in the world. GE has so far invested $175 million (Rs 740 crore) in the centre.

"I am the only foreigner here," says Managing Director Guillermo Wille with quiet pride. Almost 80 per cent of the people at the centre were hired locally, the other 20 per cent abroad -- Indians who wanted to come back.

Born in Bolivia, educated in Germany, Wille is actually as Indian as one can get. He drives a Royal Enfield Bullet, serves excellent Indian food at home, is known to be partial towards kaju katli and, if his colleagues are to be believed, has a prayer room at home, complete with Ganesh idols, marigold flowers and incense sticks.

Every GE assignment is for two or three years but Wille has completed eight years in Bangalore.

He says the objective of the centre is to use the pool of scientific talent in the country. To save cost and time was the first brief to the centre.

"The idea is to cut out the need to develop prototypes," says Wille. This can now be done with computer analytics.

And this is what, to a very large extent, the GE employees do in Bangalore. The work done here is for aircraft engines, turbines, water treatment plants, diesel locomotives and healthcare instruments, to name a few.

In addition, there is a 400-strong team that carries out work on 'Blue Sky' technologies -- new substances, materials, nanotechnology and solutions.

This team has developed the world's first pedestrian-safe bumper using an energy absorber resin just inside the fascia. Suzuki has already bought this technology for use in some cars, including the Swift, in Japan.

The 240-metre round synthetic roof over the Shanghai Railway Station which stands with no pillar support was designed and developed by the same team with the use of proprietary Multiwall sheets.

In the works is a special paint (super hydrophobic) that will not let ice settle on aircraft, especially the engines. Another team is studying stress in metals and how to reduce it before cracks appear.

Aviation

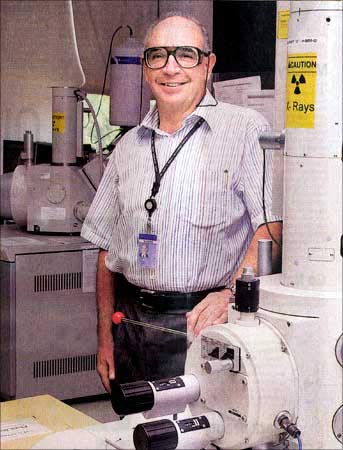

Bansidhar Phansal-kar leads the 500-strong aviation team at the centre. Three-quarters of his people hold at least a Master's degree.

These days, they can be found working on two next-generation engines: The LeapX which will be launched between 2012 and 2015, and an open rotor engine which could be commercially launched some time in 2020. It could be 30 per cent more fuel efficient than engines currently in use.

Phansalkar's job is to answer all the what-ifs that come up during the development of the engines. Over 40,000 parts make an engine and any one of these can go wrong. Its impact on the safety of the passengers needs to be assessed.

Tests simulated on computers by the team on GEnx, GE's latest engine which will power the Boeing Dreamliner (GEnx-1B) and Boeing 747 (GEnx-2B), were accepted by the Federal Aviation Authority of the US -- the first time this has happened.

"You can get 10-15 smart people at one place. It is not possible to get 500 smart people anywhere else," says Phansalkar of his team. "Ours is one of the strongest high-powered computing backbones in the country. It is among the top 15 sites anywhere in the world."

Healthcare

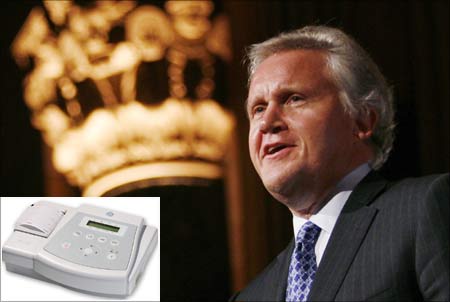

Ashish Shah left Gujarat after he got an engineering degree in the 1980s. He has spent his entire career with GE Healthcare, the last two-and-a-half at the Bangalore centre, driving the development of low-cost products for emerging markets. With 1,100 people, it is GE's second-biggest healthcare research site after Milwaukee in the US.

Though his team has come up with six such products and 10 more are in the pipeline, the centrepiece of its achievements is the Mac 400, an electrocardiogram that weighs only 1.1 kg, costs around $800 (approximately Rs 38,400) and requires less than an hour's training to operate. "It will become the stethoscope of cardiologists," says Shah.

To study the market, a dozen-strong GE team had fanned out all over the country to meet some 70 prospective customers -- cardiologists, doctors, nurses and chemists.

The result showed that patients were happy to pay a dollar (Rs 48) for a test and the electrocardiogram would find a market if it is priced not more than $800.

"We picked up technology off the shelf," says Shah.

For example, the printer in the machine is what the Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation uses for printing tickets. A battery was provided, keeping in mind the frequent power cuts in the country.

Just five buttons were kept to operate the electrocardiogram for simplicity of use. "But we did not strip it down. We have embedded our proprietary Marquette 12SL algorithm which is the gold standard in electrocardiograms," Shah adds.

GE has already sold close to 6,000 such devices. It has even been readied for the retail market in the United States. Shah's next target is to knock off another 200 gm from the machine and provide a USB port so that data can be transported. "We don't do reverse engineering. The philosophy is to go for frugal innovation."

Transportation

Worldwide, freight trains are pulled by diesel locomotives and GE is their largest producer. To service this market, it launched the Evolution Series of locomotives in 2005.

The Bangalore Centre was involved from conceptualisation to production. It played a key role in the performance simulation of the engine and rotor design dynamics for the turbo-charger. It has also designed several sub-systems for the locomotive.

The Bangalore centre works seamlessly with the core locomotive team of GE at Pennsylvania in the US, which also houses the factory.

"The drawings I clear go straight into the factory at Pennsylvania," says Vageesh Patil who studied at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore and then worked for the Defence Research & Development Organisation where he last worked on the Tejas light combat aircraft project and now heads the transportation team at the Bangalore centre.

According to Patil, in the last four years, his team of 400-odd engineers has brought down the cost of these sub-systems by up to a quarter. It will design a third of the sub-systems for the hybrid locomotive of the Evolution Series which is likely to launch next year.

For India, Patil and his team had worked on a special locomotive on the Evolution Series platform. The design was done keeping in mind the specifications given by the Indian Railways.

The end product, which was ready in six or seven months, was smaller but with the same power as in the US. But it came to naught. Since GE was the sole bidder, the bid was scrapped. The Railways have decided to build the locomotives on their own.

Energy

"We have contributed to every GE energy product," says Alok Nanda, another hand hired by GE from DRDO, who leads the 1,150-strong energy team at the centre. (Another 685 operate out of Hyderabad and Mumbai.)

The range covers turbines, crude oil extraction, water treatment and alternate energy. It started in 1999 as a centre of excellence for analytics. Since then, its scope has been substantially augmented to include product design and development. It is thus now called the Bangalore Engineering Centre.

Still, some people at the centre worry that the people do not get to work on actual machines. "The feel for steel is not there," says Phansalkar.

This, the centre realises, could sap employee morale. Wille says that the employee turnover rate of 8 per cent per annum is too high. Scientists are required to hang on to projects for longer. His own target is 3 per cent.

To address these problems, Phansalkar and his team are working on a physical engine which may never fly. Cash rewards have been instituted for innovations, though all patents are owned by GE.

Healthcare scientists are sent on 'bubble' assignments abroad. A technical career path has been devised for the technologists to match the managerial career path.

About himself, Wille says: "This is the best job in the world. There is no other job where you get to look in to so many categories."