At an exclusive and select roundtable with corporate executives, educators and administration officials, hosted by the US-India Business Council, India's Human Resource Development Minister Kapil Sibal last week contended that it is not simply US foreign direct investment by corporates in India's higher education sector or even the quadrupling of the number of Indian students in the US, that is a panacea for the demand for highly-skilled professional human resource that it inevitable in the global service economy.

At the outset in introducing Sibal, USIBC President Ron Somers exhorted the corporate executives and educators present as to "how can US investors and US educational institutions make constructive contributions to the Indian educational sector?"

Somers argued that "indeed, we all have a major stake in answering this question," and pointed out that "our member companies have major operation in India, many have major workforces there, and some like GE, have R&D facilities in India, and more and more US firms have fully integrated India into their global supply chains."

Noting that "India itself has a bounty of youthful talent 54 percent of the country is under the age of 25, and that's more than 600 million people and this is a rich resource of human talent," he said, "the demographics are squarely in favour of India, and of doing more business with India, particularly in the education sector."

Somers continued that "the US educational institutions have a pre-disposed attraction already for Indian students," and spoke of the nearly 100,000 Indian students who come to American universities and campuses each year, which "we would like to see not double, but quadruple."

Thus, he declared that "it's truly incumbent on all of us now, on how we advance this education sector together," and reiterated, "so, I return to the question, how can US investment, how can US educational institutions make a constructive contribution to the Indian educational sector."

Sibal immediately said he wanted to "turn that around, because it's not about US investment in India in the field of higher education it's about the growing importance of knowledge in economic development. Because in the new knowledge economy, it's solutions through research and technology that are going to take a nation forward that apply to India, that apply to the United States of America, that apply to any part of the world."

"So the question that we need to look at is not how much of a role the US business community can play in India in the education sector, (but) it's as to how India and the US can work together in building a knowledge grid that will help communities at both ends to give an impetus to the global economy, which will be the only sure road to peace and security."

Sibal said if one looks at the global community, there is 480 million people in all of Europe, 300 million in the US, which is still less than the 1.1 billion in India. "And, if you add the numbers in China, then you naturally come to the conclusion that there is enormous human resource available in that part of the world, which will have to be empowered if we are going to move forward to tackle some of the global challenges that we are all going to face in the 21st century."

"And, in India, in the year 2020, the average age of an Indian would be 29 that's of a total of more than 1.1 billion people."

Sibal then implied that one doesn't have to be a rocket scientist to read the tea leaves in that "if the global economy is truly global as we truly live in a global village then naturally in a declining demographic situation, somebody is going to have to fill the vacuum. You will need engineers in Europe, you will need doctors in Europe .and the same is true of the United States of America."

He said when he met US Education Secretary Arne Duncan, he had told the latter that in the US in 2009, 75,000 students took up engineering post graduate but that "in Bangalore alone, there were 65,000 students who took up engineering courses, and the figure for all India is around 650,000."

"And the fact of the matter is that in times to come, you are going to need more engineers, more doctors, in time to come, you are going to need let me put it human resource, which is quality human resource in different sectors of the economy to be able to make the economy work and get back to the growth rate that we are talking about if America is to recover from the recession."

Sibal said from India's standpoint, "We need opportunities for our economy to be absorbed in that developmental process."

Sibal explained that India has a policy "of 100 percent foreign direct investment in education. You can go into the country and set up an institution with a 100 percent FDI, but the problem is there is no framework, there is no law in place, and so a lot of informal collaborations are taking place between foreign education providers and Indian education providers without the sanctity of a legal framework."

"And, there are lots of people in that process, who are not the kind of people that we would like to be in India who provide the kind of education that we are looking for. So, it's not a win-win for either," he said.

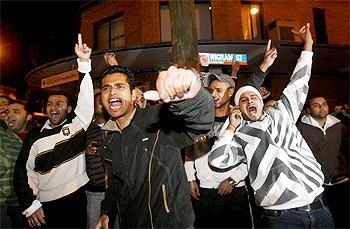

Warning of what can happen sans a legal framework, Sibal said, "You must have heard of what's happening in Australia, with a lot of the Indian community going to Australia, the kinds of attacks that have been taking place in Australia."

"It's because there's an absence of the law. Young people are persuaded to go to Australia with hope and with the expectation that they will be put in educational institutions so that they get some kind of training, so that they can get jobs and employment," he said. "But these are players who are not interested in education at all."

Thus, he warned that "if we go along that route, we are not going to be able to produce the human resource that is required by both you and us."

"So, today, what we need to do is sit down together at both ends and to ask ourselves the question, what is it that we need to provide an ecosystem that will help us move together," Sibal said, adding that was the reason for his visit to the US.

Taking issue with Somers on yet another point, Sibal said "increasing the number of students coming from India to study in the United States doesn't not only solve the problem, that's not a good economic model."

"How many Indians can afford to come to the United States?" he asked. "And if you look at the Indians coming to the United States, most of them are from the IITs, who come here, go to Silicon Valley, produce work for India, but they won't be part of the workforce that I am talking about that the global community needs that even industry needs to expand to get that growth of 3,4, 5 percent."

"That's not where it will come from," Sibal said and argued, "the Indians in the United States of America are not going to help your economy move. Your economy is going to move if you are able to get workers at low cost in the outreach areas of the world where your industry is present, whether it is in the automobile sector or in the service sector, or in the pharma sector or in the hotel sector or any other sector in the economy."

"And that's not going to come about by getting people from India, and so, I don't think that's a good service model," he reiterated. higher education institutions that is going to take place."

"So, if you come to India and set up an institution, instead of having Indians come to the US, that's a great economic model, because you can actually educate 10 times the nimber at one-tenth the cost."

Sibal said "that's a great win-win for both because whoever you want, they will be absorbed in your economy, and whoever we want, will be absorbed in our economy because the opportunities are global the opportunities are not national anymore. And, the opportunities will continue to be global because both the service sector and the manufacturing sector will have to move wherever they find the most competitive price to be in."

He predicted that he was sure that "they are going to move at some stage from India to Africa as the economy gets booming there, but that's going to take some time."

During the interaction that followed Sibal made clear that "if you are a private, foreign unaided provider, you will be governed in the same manner in which private, unaided providers are governed in India, where there is no government interference, either in terms or in terms of quotas."

However, he acknowledged that "we would like such universities to have the kind of affirmative action that they do in the United States of America themselves. So any foreign university, to be a successful venture in India should be sensitive to the needs of the community and in that context, the architecture that you bring to India, must and should, I would imagine and I would persuade you to think of that have a framework within which those concerns can be looked at."

Sibal also said India would prefer the foreign education providers come at the post-graduate level. "That is our preference and the preference is because of the fact that there is an enormous shortage of high quality docs and post-docs in our country, which then becomes the breeding grounds for providing the faculty for the enormous growth of higher education institutions that is going to take place."

When Michael Gadbow -- former vice president, GE, and now an adjunct professor at Georgetown University who formed the India Interest Group more than three decades ago, which preceded even the USIBC -- asked what role there would be for private, for-profit entities, Sibal said "the government would have no problem with peripheral activities that are always for profit."

"We are talking about core education that not for profit. All other ancillary activities are certainly for profit. There is no confusion in our minds on that issue," he said.

Sibal said there would be absolutely no "interference in curricula, faculty."

However, in terms of non-interference, he argued, "We don't expect foreign institutions to actually start charging exorbitant fees because then it would not be a win-win for both."

Since "the purpose of coming into the country is having access to that human resource, and if you fix your fees at a level that the human resources has no capability of paying," Sibal said, "then you distort the very purpose of coming in. So, you should be sensitive to the needs of India."

"In a room full of private equity investors," Somers said, "we clearly have to make money with our investors because I believe there is a tremendous resource that we bring with private equity."

Thus, he asked whether these private equity investors for example, build a college campus and then lease it to the endowment or to the educational institution, to which Sibal replied, "Why not? We can try that model. We are trying it in the private sector today."

"I mean, in school education for example," Sibal explained, "we are building about 6,000 new model schools in India, 3,500 publicly and 2,500 for public-private partnerships. Now, we are telling the private sector, you build the schools, we'll give you annuity payments for the infrastructure."

"Instead of going to a bank," he said, "we'll tell private equity to participate in the process. You get your annuity payment. The children will come from us. We'll pay you part of that money. You manage the school as well."

"If we can do it in the school sector," Sibal said, "we certainly can do it in the university sector, because we need to think of innovative ways of financing education and I don't think government can do it on its own."

When questions of reservations came up and the controversy it has generated, the minister said it was important not to get affirmative action as practiced in the US confused with reservations. "Private, unaided educational institutions are not subject to reservation policy in India."

"So, a foreign education provider, who is privately unaided, but foreign, the law can't be different for you," he added.

Indian Ambassador Meera Shankar, who also participated in the roundtable, when the question of fees came up, said it was a global market and the US has to compete for Indian students.

She said that Australia attracts as many Indian students as does the United States "and Canada and the UK also gets quite a large number."

"The Australians," the ambassador said, "have succeeded in attracting almost the equivalent to the US because they are more affordable for Indian students."

Somers jumped in, saying this was a good point and also added, "We have State Department people here as well," and they should significantly increase the number of student visas allowed each year for Indian and foreign students."