| « Back to article | Print this article |

Economic downturn sees an upsurge in labour unrest

Sam Thomas, looking dapper in his red tie and half-sleeve striped shirt, hardly shows the nervousness of a man who has been sacked by his employer. A couple of days before the pilot finally forced a reluctant Jet Airways to reinstate him after a five-day "sick out" - the official term for mass sick leave by 650 of his colleagues that crippled India's largest private airline, Thomas told Business Standard he was "fighting for dignity and not money".

If Thomas represents the new face of India's trade union leaders (he is the joint secretary of the National Aviators' Guild or NAG, the union of Jet pilots), the old guard isn't short of new-found confidence either.

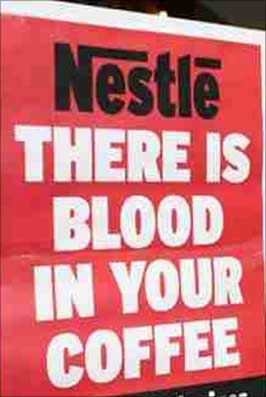

The past year has seen a rising incidence of labour strife in India, with strikes at Hyundai, Mahindra & Mahindra, Nestle, banks and oil companies. The dissatisfaction varied from delayed wage negotiations to appointment of contract workers to summary dismissal.

Though none of these protests were as violent as the killing of the CEO of an Italian auto component maker by fired workers exactly a year ago, and the scale isn't as big as it used to be in the sixties and seventies, employers are worried by the rising employee unrest that has coincided with the downturn, which saw companies curb production and costs.

Sona Group Chairman Surinder Kapur says the strikes have cropped up because there's a contraction in business. "It's a difficult time to make settlements; we can't give people good increases but their expectations have gone up," he says.

Economic downturn sees an upsurge in labour unrest

Kapur, however, is quick to add that labour is generally becoming much more responsive. "Gone are the days of animosity, they are working in partnership," he adds.

Kapur may have reason to mask his thoughts, but the "partnership" he refers to is becoming less visible by the day.

Most unions attribute this to the fact that companies are increasingly using contract workers who often account for 40 to 60 per cent of the workforce. This has weakened the position of the semi-skilled permanent workers, since contract workers are willing to work for one-third of a permanent employee's pay.

The downturn led companies to curb production and costs, which meant a loss of incentives, holiday-working and overtime for workers. This curtailed their take-home salaries in many cases by 30 per cent. As incomes went down, the cost of living went up with rising prices.

"There's increasing resentment among workers, which gets channelled in other demands, stoppages and strikes," says Franklin D'souza, joint convener, Trade Union Solidarity Committee in Mumbai, which represents 20 unions.

Take the three-week strike at Nestle at its Pantnagar plant in April. Unions allege that workers at the company's plant at Samalkha in Haryana were not getting dearness allowance, while all other new plants were.

Economic downturn sees an upsurge in labour unrest

Salaries of officers have doubled or trebled in the last few years but workers, on an average, received only a 6.5 per cent hike. The company is growing by 20 per cent, paying dividends every year but there's no equity for us,'' says D'souza. Nestle, which does not have a previous history of strikes, did not reply to an email query.

Though the Nestle workers have returned to work long ago, the strike created is an environment of fear. Managers of other plants at Pantnagar say, "If it's Nestle today, can we be far behind?"

Their nervousness may not be misplaced. For example, auto majors Hyundai and M&M lost two weeks of production to strikes in May while MRF's Arakkonam unit was paralysed for most of that month.

Besides bank employees, officers of oil companies and employees of Air India, MTNL and Airport Authority have been on warpath over the implementation of new pay scales.

In many cases, disputes have risen as managements refused to recognise the majority union. Union leaders say this was the cause of strikes at Hyundai and MRF, and is also partly the case in Jet Airways. "Employers are becoming arrogant.

The formation of unions is being vehemently opposed by managements who victimise employees," says Damodaran Thankappan, vice-president, New Trade Union Initiative, an association of 260 independent labour unions in the country.

Economic downturn sees an upsurge in labour unrest

"Employers don't want unions nor do they want to have any dialogue with employees.

"The state labour departments have become impotent; the conciliation machinery is almost defunct... The government has paralysed the labour department on the plea of the employers, who now want the government to do away with inspection of labour laws," he added.

Experts say that labour, which has been neglected since the early 1990s, has been numb for fear of losing their jobs. But pushed to the wall, it is trying to fight back.

The economic crisis has acted as a trigger; a large number of small-scale and unorganised units have been closed and left thousands without jobs.

| Strike Force |

| Jan 5: Coal workers demand higher wages |

| Jan 7: Officers of oil firms strike for higher wages |

| Feb 7: NTPC employees' demand better pay scales |

| Apr 20: Workers strike at Hyundai, seek union recognition |

| Apr 30: Delhi, Mumbai airport employees threaten strike against transfers |

| May 2: Strike at Nestle, Pantnagar after probationers removed |

| May 4: Strike at M&M, Nashik after leader was suspended |

| May 9: Strike at MRF Arakkonam paralyses unit for the month |

| May 12: Strikes at JNPT, Paradeep and Cochin ports |

| May 20: MTNL seek wage hike |

| June 12: Bank employees go on strike |

| Aug 25: Air-India staff in hunger strike to protest pay cuts |

| Sep 01: Five-day doctors strike in Patna ends; claims 38 lives |

| Sep 7: Jet's pilots go on mass sick leave to protest sacking of staff |

Economic downturn sees an upsurge in labour unrest

The basic problem is the rigid labour laws that make hire and fire near impossible; as a result India Inc has developed a preference for contract workers over a steadily shrinking permanent workforce to allow for flexibility when times are bad. Hyundai, for instance, has about 3,000 contract workers against 1,600 permanent employees.

In Pune, workers of Bosch Chassis Systems India have been on strike for over 55 days, seeking better pay and working conditions for contract workers.

What's interesting is that even white-collar workers are getting unionized - Jet's pilots have formed a guild. The knowledge workers of Bangalore have founded UNITES (Union for Information Technology and Enabled Services) Professionals India.

Though these strikes and militant protests have suddenly made a splash in the media, the problems have been festering for some time.

"Over the last two decades, the bargaining power of unions and structure for negotiations has broken down," says a Mumbai-based trade union observer.

As salaries kept increasing in the boom years, workers were not complaining.

But as soon as things started turning the other way, unionism has returned.