| « Back to article | Print this article |

Here's why Mumbai's infrastructure is pathetic

Some Arab tour agencies tout 'Mumbai Monsoon' packages as adventure tourism, which is a fair description. For someone who has never seen rain, a standard-issue Mumbai downpour is a life-changing experience.

Factoring in the epic Mumbai commutes, spending time in the western metro could indeed be considered the 21st century's equivalent of the legendary Victorian expeditions into Darkest Africa.

Even for diehard Kolkatans like yours truly, for whom rain and flooding hold few terrors, Mumbai in the monsoons is trying.

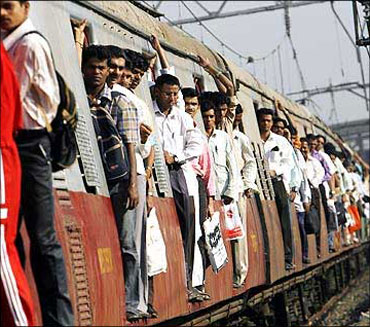

The options, if you must travel, are grim. One possibility is to hang from a train with the rain slashing down, risking decapitation, or horrific injury. The other is to allocate an hour plus for every 5 km, if you choose to move by road.

This may make Mumbai an exotic destination for tourists with time to spare. It is less entertaining for the 12 million-odd, who brave it on a daily basis. The Mumbai commute is not a pleasant experience, even in winter.

The travel time may be marginally less but the traveller usually arrives bathed in sweat, shaken, stirred and jolted by an uneven ride.

This is because Mumbai's infrastructure sucks.

Click NEXT to read on why Mumbai and other urban centres are in a miserable state. . .

Here's why Mumbai's infrastructure is pathetic

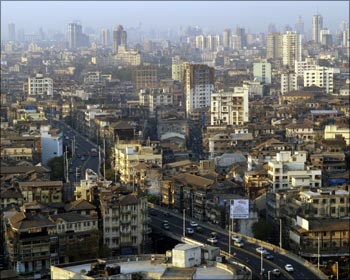

The roads and expressways could be more accurately described as moonscapes. The drainage system is appalling. So is telecom connectivity, especially during the monsoons, when dropped calls exceed completed ones.

This is not because the city is short of money. It generates a disproportionately high percentage of tax revenues. Many of the folks hanging out of First Class compartments, and queueing up for cabs at the Bandra Kurla Complex, earn six-figure salaries.

Ludicrous land prices suggest that the Mumbaikar has higher per capita than the New Yorker.

However, the wealth of Mumbai's citizens doesn't translate into better infrastructure. It never will, and there is not much they can do about it. This is because of the gerrymandering inherent in Indian electoral politics. In India, the rural vote counts for much more than urban votes.

The revenues of Mumbai are controlled by politicians, whose constituencies lie deep in the Maharashtra hinterland. Using that money to improve living conditions in Mumbai would do nothing to help them win re-election.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Here's why Mumbai's infrastructure is pathetic

So, beyond taking their turn at the feeding trough, they see no necessity to overhaul city infrastructure. Nor can the Mumbai municipal agencies raise debt by issuing bonds or securitising their own revenues because the city is tied to a state with poor finances.

Mumbai is an extreme example. But all of urban India suffers from the same problem. Infrastructure is uniformly poor, ranging to terrible.

Urban revenues are controlled and allocated by politicians, who have little interest in the urban landscape.

At the same time, more and more people are migrating to urban areas. So, the pressure on existing infrastructure is increasing. The cities attract people because they offer more income opportunities. In turn, those people generate more revenues for cities.

The only way to improve urban infrastructure is devolution of power to local authorities. The British model does seem to work to a large extent with city councils raising and spending their budgets.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Here's why Mumbai's infrastructure is pathetic

The Americans do something similar and the mayors of major cities are big wheels.

Devolution makes local authorities more powerful as well as more answerable to locals. Oddly, India's politicians have seen the utility of devolution when it comes to panchayats.

It's also worked well in the city-state of Delhi, where the state government empowered residents' associations through bhagidari.

If some version of devolution isn't implemented soon in major cities, we may see a situation where India has well-administered villages with small populations, while most people live in anarchic, urban slums.

Paradoxically, the city-dwellers will have more money but they'll have a lot less in the way of amenities.