| « Back to article | Print this article |

Obama's India opportunity in higher education

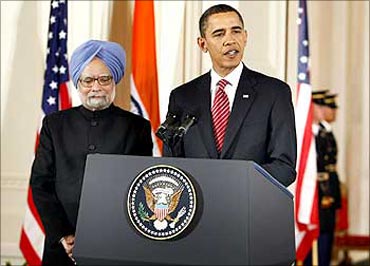

A major 'deliverable' for Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's visit last year to the United States was the launch of the Obama-Singh 21st Century Knowledge Initiative.

At the conclusion of the strategic dialogue, the US and India announced that the Initiative would provide $10 million in combined funding for the development of higher education cooperation, chiefly in the area of faculty training.

Unfortunately, very little of this is 'new' money.

Even if it were, Indian higher education expansion plans will require far more than $10 million.

Significantly greater effort, attention and resources are going to be required for this initiative to contribute significantly to strengthening the US-India relationship.

President Barack Obama plans to become the fifth US President to visit India during a trip scheduled for November.

Click NEXT to read on...

Obama's India opportunity in higher education

A presidential mission often acts as a 'forcing function' for policy initiatives. India and the US have staked much on enhanced engagement in higher education.

Thus, now is the time for both sides to undertake the actions that can provide reality to their pronouncements on US-India cooperation in higher education.

During his US visit for participation in the strategic dialogue, Minister of Human Resource Development Kapil Sibal startled audiences by stating that India needed hundred more universities and thousand more colleges by the year 2020.

If India is to fulfill its dreams of becoming a knowledge and innovation superpower, growth of this magnitude is not simply desirable but necessary.

More than any other major developing nation, India has premised its economic growth on services requiring higher education.

Currently led by information technology and information technology enabled services, biotechnology and life sciences are planned as the next wave in India's progress toward economic superpower status.

Click NEXT to read on...

Obama's India opportunity in higher education

With a population of some 1.2 billion, India is counting on a 'demographic dividend' of youthful citizens - 54 per cent of the population under the age of 25 and 70 per cent under age 35 - to propel the nation into global economic leadership.

However, this dividend will become a detriment unless there are sufficient highly educated citizens to lead the charge in science, technology, business, and the professions.

Considering that India's Gross Enrolment Ratio in higher education is about 12 per cent compared to a world average of about 23 per cent and a US GER of 82 per cent, India's need for higher educational services is manifest.

Large numbers of potential higher education students with access to private funds together with increased public budgets indicate the economic demand for such services is high in India but presently lagging projected needs.

Obviously, the US has its own needs in higher education. Twenty-two of America's top 30 growth sectors require higher education.

While the recession has increased enrollments in community colleges, many public colleges and universities are operating at less than full capacity.

There is considerable indication that the recession is having a harmful effect on US higher education as a whole.

Like any other economic endeavor, US higher education needs growth to thrive. Major economic growth is in the big emerging markets like India, not in the US, Europe, or the other mature economies.

The US institutions of higher learning need to maintain or regain their positions as the world's leading research institutions. The human resource capabilities in India are attractive for supporting this effort.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Obama's India opportunity in higher education

A significant portion of the government of India's strategy for meeting Sibal's projections for additional institutions of higher learning is now premised on foreign and, more specifically, US involvement in Indian higher education.

The US is basing a significant part of its 'next level' of US-India strategic engagement on this opportunity.

The US-India strategy can only work if there are sufficient incentives to prompt US institutions of higher learning to enter the Indian market.

The success of the strategy will also depend on sufficient benefits to Indian higher education stakeholders to overcome the traditional political opposition to foreign participation and the use of market incentives in higher education.

The planners of President Obama's visit to India should concentrate on putting these incentives and these benefits in place.

If this is done, then the US and India can demonstrate during the trip the fruits of vastly expanded US-India engagement in higher education.

Thus far, US-India governmental actions to promote engagement in higher education have focused on process rather than results. To have a lasting impact, there must be a 'demonstration effect' that can only occur by showing substantive achievement in US-India engagement on higher education.

As recently as 2007, India's ministry of human resource development opposed the independent participation of foreign institutions in Indian higher education.

Click NEXT to read on...

Obama's India opportunity in higher education

This policy was reversed this year with the stated intent of 'facilitating the participation of globally renowned and quality academic institutions in our higher education sector ' Legislation to implement this change in policy is pending in India's parliament as the Foreign Educational Institutions (Regulation of Entry and Operations) Bill.

The FEI Bill is important in allowing 100 per cent foreign direct investment in higher education entities and providing the policy framework for such endeavors.

However, political opposition has forced the government to include provisions that may provide disincentives to increasing the level of US-India engagement in higher education.

The US and India will have to find legitimate and politically acceptable incentives for the US institutions of higher learning to participate in India if US-India educational engagement is to make the kind of contribution to Indian higher education that both governments contemplate.

The rather minimal governmental funds available from both sides will not provide the needed resources, and the private sector, on its own, is unlikely to make the required investments.

The US and India should develop a replicable public-private model that shows US-India engagement on higher education can work.

Fortunately, in conjunction with the upcoming Obama visit, there is a mechanism that if properly utilised could produce such a result.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Obama's India opportunity in higher education

As a part of the Obama-Singh 21st Century Knowledge Initiative - and at Sibal's suggestion - the US and India have promoted a private sector US-India Higher Education Forum.

Such a forum can make a significant contribution if it is directly and strongly connected to resources and policymakers in both governments.

Such a connection should be made now in preparation for the Obama visit to India.

A strong public-private partnership with suitable funding focused on one or more demonstration projects could open the floodgates of US-India engagement in higher education.

President Obama's mission to India provides an ideal opportunity to benefit the US, India, and their institutions through vastly increased engagement in higher education. Now is the time to seize this opportunity.

Raymond E Vickery, Jr, assistant secretary of Commerce, Trade Development, Clinton administration, is senior director, Albright Stonebridge Group LLC, and Woodrow Wilson Centre Public Policy Scholar 2009