| « Back to article | Print this article |

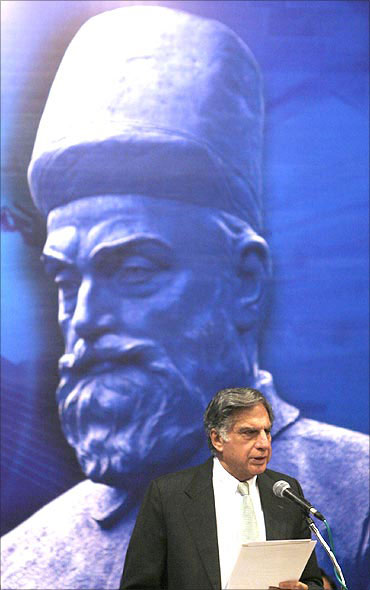

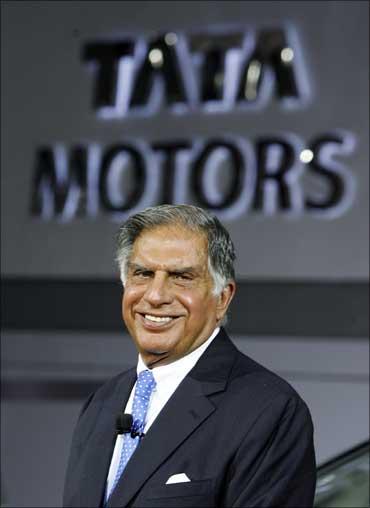

What must Ratan Tata's successor be like

Ever since the Tatas announced the formation of a committee to select a successor to Ratan Tata there has been constant speculation over who will become the new Tata chief!

Given the size, geographical spread and complexity of the Tata empire it would probably be easier to nominate India's prime minister than to find a chief executive for the Tata Group.

But first some background information on the Tata Group. In 2008-09, the group's revenues stood at Rs 325,334 crore or $70.8 billion, with 65 per cent of it accruing outside India.

The Tata Group employs 363,000 people and has 28 publicly listed companies. It is divided into seven business segments namely Communications & IT (14% TCS, Tata Communications), Engineering (24% Tata Motors, Jaguar), Materials (45% Tata Steel, Corus), Services (3% Taj, TAIG), Energy (6% Tata Power), Consumer Products (3% Tata Tea, Titan, Trent) and Chemicals (4% Tata Chemicals). The figures in the brackets are the percentage of group turnover and key companies under that business.

You can see that the Tata Group is present in diversified lines of business from cars, steel to selling books and air time, not to forget new areas like manufacture of helicopters.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

What must Ratan Tata's successor be like

Two-thirds of the Tata promoter company, i.e. Tata Sons, is held by philanthropic trusts. The Group Executive Office (5 members) and Group Corporate Office (7 members) define and direct the business endeavours of the Tata Group.

The former's chief objective is to increase synergy between group companies, while the latter reviews and discusses broad policy issues relating to growth and entry into new growth areas. Every company has a managing director and a board.

Five core group values are Integrity, Understanding, Excellence, Unity and Responsibility. Above all the name Tata symbolizes TRUST.

Ratan Tata is on the boards of Fiat SpA and Alcoa and on many international advisory panels. He is a member of the Prime Minister's Council on Trade and Industry and the British PM's Business Council for Britain. By education he is a qualified architect.

After the low-cost sensation, the Tata Nano, and low-cost water purifier, Swach, one has begun to associate innovation, or its Indian name jugaad, with the group.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

What must Ratan Tata's successor be like

From the above a few things come out clearly. The Tata Group is a diversified conglomerate with strong presence across continents. The companies are run pretty independently. Centrally, there is a great degree of focus on building the Tata brand and exploring group synergies.

Integrity is a key group value. Giving back to society is an important aim of the Tatas. Unlike other business houses there is no large or extended Tata family.

The 'outgoing' chairman Ratan Tata expects the group to be much bigger than it is now in India and outside. He hopes that "the group comes to be regarded as being the best in India -- best in the manner in which we operate, best in the products we deliver and best in our value systems and ethics."

It is today a well-knit cohesive group unlike what Ratan Tata inherited where he had to fight corporate satraps to first establish his hold over the company, reform it, imbibe it with group values, give it a Tata identity and take it to the next level.

Now what should the profile of Ratan Tata's successor -- called CEO, for convenience -- be.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

What must Ratan Tata's successor be like

The person should have presence and stature. A requisite since the CEO would have to interact with corporate leaders globally and heads of state in India, the United Kingdom, et cetera.

Should the Group CEO be a specialist? The Tatas have specialists to manage individual companies so the CEO should be a generalist with excellent people management skills. These would be put to test in dealings with senior colleagues, politicians, world leaders and diverse employees worldwide.

Ratan Tata might have got away at times by virtue of his being a Tata. The CEO might not necessarily have this luxury and should have the ability to manage the boardroom and carry the team with him at all times.

Note that 18 per cent of the promoter company, Tata Sons, is owned by the Shapoorji Pallonji family who would like to see the value of their investment increase. Hence they will monitor group performance more closely.

Should the CEO be an Indian? The group needs to hire the best available talent. If a non-Indian heads the group, the CEO would need to understand the Indian way of working.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

What must Ratan Tata's successor be like

The CEO should be a visionary and must understand how the global economy is going to play out in the next 12-15 years. Based on that, he should be able to determine the strategic footprint for the group to take it to the next level.

Since 69% of the Tata Group's turnover comes from engineering and materials should the CEO have an industrial manufacturing background? Not necessarily, but such a background would help. After all, adapting technology to emerging markets has been one of the Tata Group's strengths.

It is very important for the group not expect the CEO to be a clone of Ratan Tata and not to constantly compare him with Ratan Tata. Just like there can only be one JRD Tata so also there will only be one Ratan Tata.

The CEO should have a personality strong enough to leave his imprint on the group.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

What must Ratan Tata's successor be like

The CEO should have:

- Impeccable public integrity and image. You can trust the media to investigate the CEO's background from the moment he was born!

- A track record that inspires respect.

- Be able to spot opportunities and the next big idea, strategise accordingly and ensure execution.

- Run global organisations and managed a set of business portfolios.

- An understanding of how decisions are taken in the Tat Group and accept it as it is rather than try to create a different culture which is bound to result in friction.

- The ability to realise that the Tata Group and its people could be pretty set in their ways. Instead of trying to change them the CEO should find ways to enhance performance.

- The ability to believe that people are assets who have to be nurtured and developed not retrenched at the hint of a downturn.

- The ability to acknowledge that one of the group's focus area is the climate change crisis.

- The ability to accept that the group is deeply committed to philanthropy.

- The ability to export the group's innovation worldwide.

- The ability to convince the board to induct younger and outside talent in the group corporate office.

- The strength of character to stick his neck out by saying that the group would, say, produce the Future Infantry Combat Vehicle (FICV) for the Indian Army at lower costs and comparable quality with the best in the world.

- The ability to be unemotional and be able to hive off businesses that are not the focus areas for the Tatas.

- An understanding of state politics to avoid another Singur-like fiasco.

- The ability to effectively communicate with the media, especially in India where he would be under intense scrutiny.

- A network of contacts with world leaders in defence products and energy.

- An understanding of the African market that would assist the Tatas in capitalizing opportunities there.

- The ability to work towards having a larger number of women on the boards of Tata companies.

- The ability to internalize and promote the five core values of the Tata Group.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

What must Ratan Tata's successor be like

Deep down, some rich Parsi families have never forgotten that it was India that gave their forefathers refuge when they were being persecuted in Iran. Their nationalistic and philanthropic approach in India could arise out of a feeling of gratefulness.

The CEO would need to relate to this feeling more so if he is not an Indian.

A non-Indian CEO needs to:

- Know that heads of businesses in India are as much concerned about financial results as they are about social issues and national well being.

- Know that improvisation and adaptability are at the core of what is called the Indian way of doing things.

- Realise that Indians are relationship-oriented more than transaction-oriented.

- Realise that Indians are forever looking out for 'value for money' buys.

- Understand what unites India is cricket and Bollywood.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

What must Ratan Tata's successor be like

It is not clear what Ratan Tata's role would be after he steps down as chairman of Tata Sons. Would he become the non-executive chairman of Tata Sons? How his role is defined and played out is the key. Would the incumbent be designated as chairman of Tata Sons or Group CEO?

This is probably the most interesting and keenly watched leadership change that shall be effected in post-liberalised India. Ratan Tata's tenure as Tata Group chairman can be a wonderful case study in organisational change and enhancing shareholder value.

It would be very interesting to capture the process of leadership change in the form of another case study as to how a diverse conglomerate goes about planning and executing this change. Whether this case study would be an example of a successful change is something only time can tell!

The author is a management consultant and cross cultural trainer.