| « Back to article | Print this article |

An organic farming guru's success story

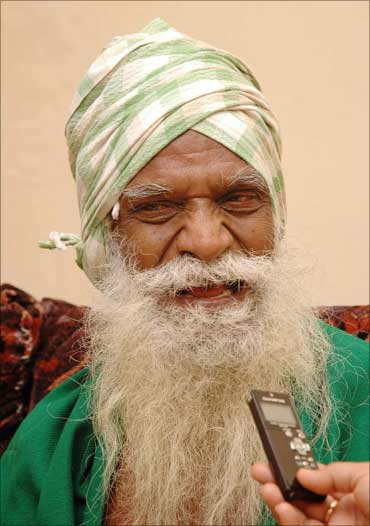

Organic scientist G Nammalvar chose to dedicate his life to the upliftment of farmers in India and organic farming, after studying agriculture science.

Dr Nammalvar, who is known as the 'Father or Guru of organic farming' in Tamil Nadu, was born to a farmer's family in Thanjavur.

Though he grew up in the green belt of Tamil Nadu, he chose to work in the driest areas of the state. Three years ago, Gandhigram Rural University bestowed an honorary doctorate to this 73-year-old visionary.

G Nammalvar shares his success story... Click on NEXT to read further...An organic farming guru's success story

I hail from a huge farmer's family in a village that is 30 kms away from Thanjavur and was the youngest among the siblings. Thanjavur was the green belt of Tamil Nadu thanks to the Kavery river.

I used to go to the fields to work before and after the school. I was surrounded by the green carpet of crops. We also used to sleep with the cattle. That was the kind of life I led when I was a child.

My elder brothers wanted me to study science as they felt there was future only in Science. But I had a strong liking towards Agricultural science. At that time itself, I knew that India's future lies in agriculture. I thought I could make myself useful to more farmers in the country if I studied the scientific methods in farming.

Thus farming and agriculture became a part of my life. I could not even think of doing anything else. So I joined Annamalai University to study Agricultural science.

After my graduation, I joined the Agricultural Regional Research Station at Kovilpatti as a scientist. It was the first agricultural research station started by the British in 1901. Kovilpatti is the driest place in Tamil Nadu, I would say. Coming from the greenest part of the state, it was a rude shock and a challenge to me.

I was doing trials on spacing and manure levels of various chemical fertilizers in cotton and millet crops. All the crops like Jowar, bajra, ragi, millets, pulses, cotton, etc. which I tried out there came out very successfully.

There were experiments on rain fed land about the usage of hybrid seeds, chemical fertilizers and chemical pesticides. I felt the experiments were futile as the rain fed farmers were resource poor. I wanted to reorient the research work but was not successful. Frustrated, I left the institute.

An organic farming guru's success story

I spent the next 10 years as an agronomist at the Island of Peace, an organisation founded by the Nobel Laureate R. P. Dominic Pyre. My focus was on improving the standard of living through agricultural development of Kalakad block in Tirunelveli district.

I was in charge of the black cotton soil farm there. As we were in a low rainfall region, the farmers used cattle manure as fertiliser. They also kept sheep and cattle on the soil so that their urine and dung added fertility to the soil. I was instructed to add fertiliser and compare the results.

By using chemical fertilisers, I found that farmers only incurred loss and the cost went up. I wrote to the authorities that if chemical fertilisers were used, soil would be spoilt and farmers would be ruined.

If you apply chemical fertiliser, you need to provide more water, or else, the plants will wilt. I realised by then that in order to get optimal results in farming, farmers should rely minimally on external inputs like fertilisers, and all inputs should come from within the farm. This was a turning point in my life.

In fact, I lost trust in the conventional farming practices and began experimenting with sustainable agricultural methods. I started Kudumbham, a society, in 1979 to spread the idea of "Participatory Development" forward.

An organic farming guru's success story

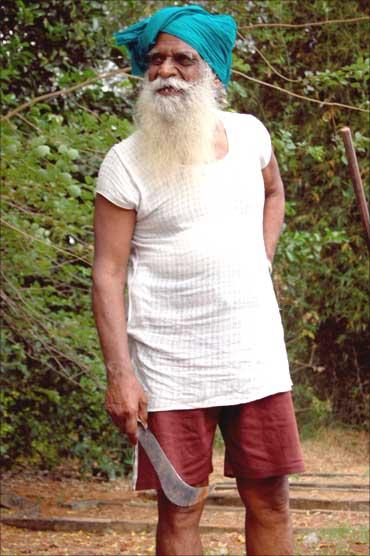

I was like a western educated man in pants and shirts. But two people - Paulo Freire and Vinoba Bhave - changed my life completely. An article by Paulo Freire in the magazine Idea and Action published by the Food and Agriculture Organisation, Rome dwelt on participatory development and participatory education, and said if you wanted to do any development for the people, you also should participate in the process.

For that, you should go to their level. So, I decided to change myself in my dress, behaviour and attitude, and be one of them.

Vinoba Bhave wrote in the same magazine that education is a process of giving and pure theoretical education is not education at all.

When I started dressing up like them, all the farmers accepted me and embraced me as one among them. They started singing and dancing with me. I then understood that I was at the right place. I went from village to village trying to learn from them, in the process teaching them too about organic farming.

What I did first was to join hands with a young farmer who had two pairs of cattle. While he ploughed his field with one, I ploughed with the other. Ploughing was not new to me as I had done that in family fields too.

An organic farming guru's success story

One day, some women harvesting ragi asked me, won't you come and join us? I said, I don't have a sickle. They said they would give me one. So, I joined them with a sickle! I harvested a ragi crop along with the women and during lunch break, I ate with them.

There was a craving in me to do something by which the farming community is uplifted.

Organic farming and Aurobindo Ashram

Another person I am greatly influenced with is Bernard de Clarke from Belgium who made Auroville as his work place. He had started organic farming there. It was from him that I learnt to do organic farming in a systematic way. If done in a systematic way, organic farming gives more food with less expense, and you eat less poison.

There was a 100-acre plot in the Aurobindo Ashram where Bernard did organic farming. The story is that Mother once asked her shocked disciples, "I asked for food but you are feeding me poison. Why?" From that day onwards, they stopped using any fertilisers, and it was purely organic farming for them. They were doing it for the past 12 years. I understood there that farming itself is a philosophy.

(In 1995 he was nominated as the Tamil Nadu state coordinator for ARISE (Agricultural Renewal in India for Sustainable Environment). Bernard was the coordinator at the national level.)

In the beginning, when I told the farmers not to use fertilisers, they were alarmed. I realised that instead of telling them, I should demonstrate and show them what organic farming is all about.

An organic farming guru's success story

I along with a few friends bought a 10 acre barren plot in the dry Pudukottai district. There was no river there and was a low rainfall area. We first fenced the land with live crops and not with cement. Then, we started rain water harvesting and planted a tree nursery.

After we dug wells, we started a vegetable garden and a poultry farm. The local boys and girls joined us in cultivating vegetables. What we did was replicate what was done as wasteland development at Auroville by Bernard.

I asked the people what trees they wanted to plant. They gave the names of 52 trees. But the names of Eucalyptus and Babul (which are planted by the government in social forestry schemes) were not there in it, and we planted all the 52 varieties.

When we first dug a well, even after going 30 ft deep, we didn't get any water but after three years, the water level went up drastically. Then, we had grass for the cattle and sheep we brought in. We also had many birds there. There was nothing that we didn't have. By now, our community farm has 20 acres of land.

From all over Tamil Nadu and other states, people came to stay there and learn about organic farming.

After making our farm successful, I started going to places in Maharashtra, Chattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh, Orissa, etc, and teaching people. I undertook a padayatra from Bhavani Sagar dam to Kodumudi for 25 days and I travelled from village to village.

From many villages, hundreds of people walked with me. After the yatra, I could make many farmers switch to organic farming. We are also popularising the need to harvest millets and have started an All India Millet network.

An organic farming guru's success story

I will give you a few reasons why GM seeds should not be used. GM seeds contaminate other plants related to the family. It will destroy the biodiversity of the soil and after that, we will not be able choose the plants that are suitable for the area and need. It is a risky science and at any point, the gene can move from plants to animals.

To control pests, we don't need GM seeds. GM seeds are not produced for the benefit of the community. The companies say GM will increase the income of the farmers. But it is not true.

The cost of the seeds is very high. It has nothing to increase the yield. When a company has monopoly, they will decide the price of the seeds, and we lose our national sovereignty. We have to look at all these points before accepting Bt crops.

I would say that what is happening regarding GM seeds is not only the problem of the farmer but also the problem of the nation too.