| « Back to article | Print this article |

Story of missed opportunities as PM goes to Japan

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh would soon be embarking on an East Asian journey that will take him to Japan, Malaysia and Vietnam, but it is the visit to Tokyo on October 24-26 that is pregnant with a sense of missed opportunities.

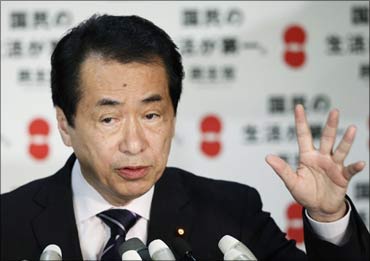

With Naoto Kan's government obsessed with its current China travails and still struggling to right its economic and political relationship with the United States, relations with India have taken a back seat.

This has also allowed New Delhi to slip the leash on several key projects, including a proposed nuclear agreement, embarking upon a second wave of economic reform and moving with greater speed on the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor.

The centerpiece of the PM's visit is a long-awaited Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement that has been through several fits and starts, including bureaucratic obduracy in Delhi.

Even in its final form, which Business Standard has seen, there remains a significant lack of transparency, with 'all service sectors' still blanketed under national treatment clauses.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Story of missed opportunities as PM goes to Japan

Nevertheless, the CEPA, covering trade in goods as well as investments and boosting the $11-billion (Rs 48,700 crore) annual two-way commerce, is expected to provide Indian goods with a foothold into the markets of East and Southeast Asia.

Indian concerns over processes and the sale of pharmaceutical drugs have been addressed, allowing for a 'WTO-plus' treatment to this sector.

But according to Srikant Kondapalli, professor in the Centre for East Asian Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, the biggest confidence-building measure between the two countries could be New Delhi's decision to pursue a second wave of economic reform, which includes allowing easier hire and fire, which Japanese business has long been pushing.

"Unless Delhi concedes on new economic reform, we won't see much Japanese activity in India.We have to realise that the Japanese want to invest large amounts of money in other countries because of the rising value of the yen at home. China, which attracts large Japanese investment, is in the eye of a storm in Japan these days. Some Japanese money has gone to Vietnam, but Vietnam is too small a country. If India plays its cards right, the Japanese could be at the forefront of a new wave of investment here," Kondapalli said.

The Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor, the showpiece of the PM's visit to Japan in 2008 but languishing today because of land acquisition problems, is a classic case of the drifting relationship, although a set of 'smart' cities have been proposed around this north-west lifeline.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Story of missed opportunities as PM goes to Japan

Kondapalli pointed out that things were going well in several strategic areas such as maritime cooperation -- including defence exercises and protecting the sea lanes -- but if Delhi could open the retail sector and unleash labour reform, Japanese FDI could soon overtake the Koreans in India. The 2009 figure of $11 bn is only four per cent of Japan's trade with China.

Nuclear, visa issues

A major missed opportunity in the impending summit will be the absence of a nuclear accord, negotiations around which were beginning to capture the world's imagination because Japan is the only country in the world to have first-hand experience of the horrors of a nuclear attack and India is one the only three countries which continue to refuse to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

There were simply too many differences which kept both sides apart on this front. While Japan wanted an unequivocal statement by India that it would not conduct any more nuclear tests in the future -- on the lines of a commitment India had given the Nuclear Suppliers Group in 2008 -- Delhi demurred, saying it needed to keep its 'strategic autonomy' intact.

As if to make up for the lack of the eye-catching nuclear pact -- which was supposed to also supply crucial pieces in the Indo-US nuclear deal, because key US companies like Westinghouse Electric Company and General Electric are either partially or fully owned by Toshiba Corp and Hitachi, respectively, and Japanese permission was supposed to complete the last mile of the 123 Agreement --- officials will sign in the presence of the two PMs, a visa agreement that will let Japanese workers in India live and work for three years at a time.

Clearly, the visa agreement is not in the same league as a prospective nuclear deal, but it will have to do.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Story of missed opportunities as PM goes to Japan

It is believed that Prime Minister Manmohan Singh had to personally push the pact over the head of recalcitrant bureaucrats in the home ministry, who questioned the need for having a three-year work visa.

It was explained to the ministry, government sources said, that a work visa for Japan was 'quite different' from a work visa for Chinese workers, many of whom had allegedly taken jobs meant for local labour.

The visa agreement is expected to benefit only about 400-500 Japanese nationals who currently work in India, mostly with car companies (many thousands more are expected when the 1,483-km Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor takes off, the first phase of which will be ready by 2018) -- but it is expected to compensate the daily humiliation that foreign nationals are subject to by the Foreigners Regional Registration Office (FRRO), Japanese sources said.

"The kind of red tape, delays and even humiliation by the FRRO that we have to put up with are to be seen to be believed," a Japanese businessman, who sought anonymity, told this journalist, adding that the proposed enhancement by one year of a work visa was 'a great thing'.

Besides, both premiers will also sign on a document on biodiversity issues which could provide a major input to the climate change imbroglio dividing the world, signal the intention to conclude a social security pact for workers in both countries, as well as promise to create a level-playing field for health care workers, including nurses.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

Story of missed opportunities as PM goes to Japan

The reluctance to exercise political will -- from a missing nuclear accord to unclear parameters around CEPA -- seems to be common both in Delhi and in Tokyo.

Back in Japan, Prime Minister Naoto Kan is being accused of passing the buck on promoting the India-Japan relationship, with Kan's critics pointing to his reluctance to push the proposed nuclear deal.

In fact, the Japanese media is full of commentary on how the real power behind the throne is chief cabinet secretary Yoshito Senkoku, the 'go-to guy' on all major issues.

From calming the Sino-Japan spat on the Chinese fishing trawler -- Senkoku is believed to have spoken to Chinese state councillor Dai Bingguo, a major power in the Chinese communist party, whom India knows well -- to deciding the seating arrangements of all those attending the banquet in honour of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh on October 25, Senkoku is being touted as the man for all seasons in Tokyo today.

Meanwhile, a top business delegation led by Reliance's Mukesh Ambani, has agreed to (it is still unclear if Ratan Tata will go) accompany the PM to Tokyo, but it is still unclear whether the outcome is worth the effort.