Suman Guha Mozumder in New York

Pranab Bardhan, professor of economics, University of California, Berkeley, has done theoretical and field studies research on rural institutions in poor countries, on political economy of development policies, and on international trade.

In his latest book, Awakening Giants; Feet of Clay: Assessing the Economic Rise of China and India, he discusses the two countries' economic reforms, patterns and composition of growth and the problems afflicting their agricultural, industrial and financial sectors.

Do the words 'Feet of Clay' in the book's title mean you find some inherent weaknesses in the economies of India and China?

Obviously. I wanted to emphasize this because in the media there is quite often a great deal of hype about both countries' economic performance. There is no doubt that there have been economic achievements, and it has been remarkable, but the weaknesses of the economies are underemphasized.

In fact, there are some myths that have developed about both these countries and the purpose of the book is to dispel them.

. . .

'Poverty in India dipped not due to globalisation'

Photographs: Reuters

China is often referred to as the manufacturing hub of the world, while India is called the service centre. Are these myths?

This is true to some extent, but one should not exaggerate.

Let me give you an example. What is important for an economist is not the total output, but value addition. To produce an output you need raw materials, components and parts and you have to deduct those values. Otherwise the total value of the output could be misleading.

If you take the value added. . . China is not the largest manufacturing centre in the world. It is in terms of output, but not in terms of what counts -- value addition. . .

If you take the world manufacturing income or the value added, China contributes 15 per cent. Japan is also about the same; the United States contributes about 24 per cent and Europe about 20 per cent. . . China will probably reach there over time, but it has not reached there so far.

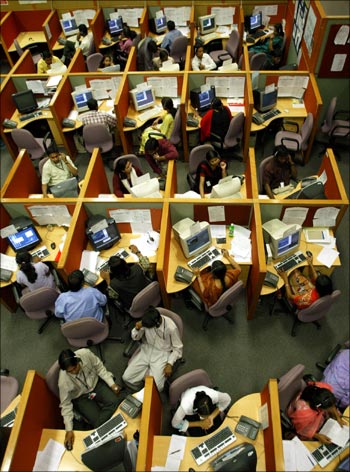

Similarly, India's economic growth is regarded as service sector-led growth. That is a big achievement for India. But when you talk about service-sector led growth, most people think of information, software technology, or business processing.

Those sectors are clearly growing at a fast rate in India. However, one should have some sense of proportion as to how much of the India's economy is involved here. All the IT-enabled servicers, including call centres and business processing, employ less than half of 1 per cent of the Indian labour force. Each job created in the service sectors may create other jobs elsewhere.

Even if you count four jobs elsewhere to each job in the service sector that is 2 per cent of the labour force. Even if you have a dramatic growth in this part of the economy, it will not easily transform the Indian economy. It is undoubtedly big compared to what we had in the past. But even today, two thirds of the total service sector income is still in the informal sector. . . Service sector is a tiny part of the total employment of the Indian economy.

This is not to deny the important achievements that have been made by the Chinese in manufacturing and India in service sectors, but we need to keep things in perspective. As I said in the book, we need to qualify the conventional wisdom.

. . .

'Poverty in India dipped not due to globalisation'

Photographs: Reuters

Any other example of qualifying conventional wisdom?

You will read in the media that there has been a very high rate of growth and large reduction in poverty in India and China. Because these two have been the largest poor countries in the world, people are impressed that poverty is going down.

And then people say that this poverty reduction has been possible because both countries have integrated themselves to the global economy. . . That is the conventional wisdom.

If you take a very crude line of $1 a day of per capita, between 1980 and 2005 more than 625 million people have been raised above that poverty line in China. But let us see how much of that happened, if at all, due to integration to the global economy.

More than half of these 625 million people were raised above the poverty line by 1980 and 1987. Global integration of the Chinese economy came in 1990s, particularly in the latter half of the decade. China became a member of the WTO in 2001.

Between 1995 and 2007 global integration of the Chinese economy took place in a big way. So, more than half of the 625 million were raised above the poverty line long before globalisation.

In India such a dramatic fall in the poverty has not happened. What happened there was that significant reduction in the percentage of people below the poverty line. I think it went down from 44 per cent to something like 24 per cent.

But since India's population was growing much faster than China's, while the percentage of people might have gone down, the total number may not have gone down.

. . .

'Poverty in India dipped not due to globalisation'

Photographs: Reuters

How did China's poverty alleviation happen?

It was a domestic factor that had almost nothing to do with globalisation. In the early 1980s, there was a big change in China's agricultural sector when the government moved from the commune system and gave cultivation rights to individual farmers.

Secondly, they distributed land rights in an egalitarian fashion. Almost everybody got equal land. . .

This has not been the case in India. To this day, in India a very large percentage of the rural population are landless or near landless.

But most Indian farmers have always owned land privately, right?

India has farmers who have held land privately for a long time, but landless or near landless farmers account for almost 40 per cent in India. In China everybody has equal land. As in China, reduction in the poverty level in India has hardly anything to do with globalisation and more to do with agriculture, including the Green Revolution from the mid 1960s.

My point is that the poverty alleviation in both these countries has not been due to integration to global economy, but because of domestic factors. Globalisation helped, but that is not the main or only factor.

. . .

'Poverty in India dipped not due to globalisation'

Photographs: Reuters

How can globalisation help in poverty reduction?

One way is if the country exports products that are labour-intensive. This creates jobs for the poor. China exports goods like garments, toys and shoes that are all labour intensive.

In India, globalisation has less of a role in poverty reduction because. . . India's success story is more related to skill-intensive or capital-intensive products. Software does not employ poor or unskilled people, nor are they labour-intensive.

Similarly, India has done very well in pharmaceuticals, but that industry is not labour-intensive. Not enough jobs have been created in India (because of globalisation) even though the country has become more globally integrated and is doing well in terms of export of these products. Globalisation helped China somewhat, but it helped India less in terms of doing something about poverty reduction.

At the end of the book you talk about structural weaknesses and political uncertainties in India and China, which may not augur well for their future. Please elaborate.

The uncertainties are much more in China than in India. It is mainly because China is an authoritarian regime. China is already having problems in terms of getting information from the lower level. China has a system where lower rung officials are rewarded when good things happen in the local economy.

Therefore, they have an incentive to not give bad news or information to their bosses. Whereas India is a democracy and the media is very active.

Another problem in China is that unlike in India there are no checks and balances against capitalist businesses becoming predatory at the local level.

Most people think China's government is strong and India's weak. China takes quick decisions and carries them out forcefully. It steamrolls all opposition, that is why it gives the impression that it is strong. Whereas India takes a long time to decide and there are lots of protests.

. . .

'Poverty in India dipped not due to globalisation'

Photographs: Reuters

The chaotic way things are done in India gives the impression that India is weak. But fact is that the Chinese government derives its legitimacy from the high growth rate; it has little other source of legitimacy.

On the other hand, the Indian government derives its legitimacy from democratic pluralism, not the growth rate. The same trouble will cause more instability in China than in India because of the latter's authoritarian regime.

One hears of predatory businesses in India as well. . .

India also has capitalists, who get away with predatory practices, but at least there are popular protests; there are NGOS (non-governmental organisations), and if politicians do not take up the issues, they know they will lose elections. This is just an example.

Another problem in China is land grabbing where authorities bulldoze your house and grab your land. This has happened quiet rampantly. By 2007, about 17 million farmers had been dispossessed of their lands, and they got very little compensation.

Land grabbing exists in India too . . .

But the victims in India are nowhere near the Chinese number. (In India) it is leading to protests and election results, like in West Bengal.

But the Indian democracy is weaker at the local level . . . quite often the local powerful people capture local governments.

India also has problems because of lack of democratic accountability at the local level. What I am suggesting is that some of these problems are happening because of lack of accountability mechanisms in both countries.

article