| « Back to article | Print this article |

If UPA government tackles inflation, it will collapse!

Economic textbooks tell us that inflation is a function of cost push and demand pull.

The former implies a scenario wherein inflation is fuelled through increase in input costs, while the later is caused by mismatches in demand and supply.

But all these have been dynamited by real life developments of the past couple of years. Let me elaborate.

Of late, there are a new class of global investors -- investment by the financial sector in the commodities futures market. What is worrying analysts is the growing influence of these players, who tend to take positions that exert extraordinary pressure on prices.

Moreover, their activities are obviously coordinated across currency, stock and commodity markets.

Crucially, these players have a symbiotic relationship with sections of the media. In the process, the traditional economics seems to have been completely turned on its head.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

If UPA government tackles inflation, it will collapse!

Examining the global situation

This issue is of particular importance for food commodities in a country like India. Nothing illustrates this paradigm better than a report by Johann Hari, How Goldman gambled on starvation, in The Independent, UK, on July 2, 2010 portions of which I am reproducing hereunder:

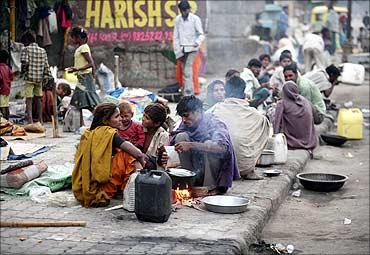

'You want to know how some of the richest people in the world -- Goldman, Deutsche Bank, the traders at Merrill Lynch, and more -- have caused the starvation of some of the poorest people in the world?'

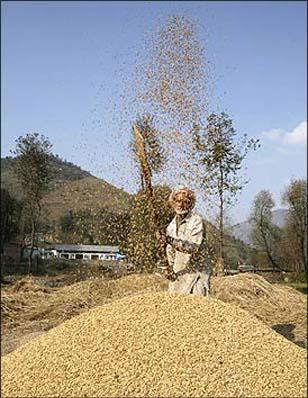

'At the end of 2006, food prices across the world started to rise, suddenly and stratospherically. Within a year, the price of wheat had shot up by 80 per cent, maize by 90 per cent, rice by 320 per cent. In a global jolt of hunger, 200 million people -- mostly children -- couldn't afford to get food any more, and sank into malnutrition or starvation. There were riots in more than 30 countries, and at least one government was violently overthrown,' the article said.

'Then, in spring 2008, prices just as mysteriously fell back to their previous level. Jean Ziegler, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, calls it 'a silent mass murder', entirely due to 'man-made actions'.'

Most of the explanations we were given at the time have turned out to be false. It didn't happen because supply fell: the International Grain Council says global production of wheat actually increased during that period, for example.

It isn't because demand grew either. As Professor Jayati Ghosh of the Centre for Economic Studies in New Delhi has shown, demand actually fell by 3 per cent.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

If UPA government tackles inflation, it will collapse!

Other factors -- like the rise of biofuels, and the spike in the oil price -- made a contribution, but they aren't enough on their own to explain such a violent shift.

For over a century, farmers in wealthy countries have been able to engage in a process where they protect themselves against risk . . . When this process was tightly regulated and only companies with a direct interest in the field could get involved, it worked.

Then, through the 1990s, Goldman Sachs and others lobbied hard and the regulations were abolished. Suddenly, these contracts were turned into 'derivatives' that could be bought and sold among traders who had nothing to do with agriculture. A market in 'food speculation' was born.

Until deregulation, the price for food was set by the forces of supply and demand for food itself. (This was already deeply imperfect: it left a billion people hungry.)

But after deregulation, it was no longer just a market in food. It became, at the same time, a market in food contracts based on theoretical future crops -- and the speculators drove the price through the roof.

In 2006, financial speculators like Goldman pulled out of the collapsing United States real estate market. They reckoned food prices would stay steady or rise while the rest of the economy tanked, so they switched their funds there.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

If UPA government tackles inflation, it will collapse!

Suddenly, the world's frightened investors stampeded on to this ground. So, while the supply and demand of food stayed pretty much the same, the supply and demand for derivatives based on food massively rose -- which meant the all-rolled-into-one price shot up, and the starvation began.

So it has come to this. The world's wealthiest speculators set up a casino where the chips were the stomachs of hundreds of millions of innocent people. They gambled on increasing starvation, and won.

Thanks to the machinations of these financial speculators, grain prices -- especially those of wheat -- rose across continents. The then American President George W Bush blamed it on the increasing consumption by the Chinese and Indians.

The Indian response was even more bizarre -- some of our experts actually floated the theory that south Indians were turning away from rice and were consuming more wheat, which was fuelling global wheat prices!

Yet no one, definitely not a single trained economist from the establishment, blamed it on financial speculators and their impact on grain prices. Either they were in cahoots with these speculators or were inexcusably ignorant about the derivatives market.

Speculator push, media pull

What is adding fuel to the fire is the role played by the media in the entire affair. Increasingly, it is being seen that the dividing line between the media and financial players is getting blurred. The media seeks to be a player in the markets while simultaneously it is also a commentator on the markets.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

If UPA government tackles inflation, it will collapse!

This makes it easy for anyone to make or mar the markets by manipulating market sentiment.

Naturally, with its power and reach, the media has enormous influence over the collective psyche of the people. This enormous influence ensures that the sentiment is always controlled -- mostly favourably, but if need be negatively -- by sections of the media.

With rumours of several media players having taken enormous positions in the stock, currency and commodity markets globally, the role of media as an independent commentator is increasingly becoming suspect.

Consequently, a 'report' published in some remote corner of the world on the El-Nino flows or its impact on the Indian monsoon pattern could well trigger a spurt in food grain prices (perhaps globally) merely on anticipation of a failure of the monsoon.

This speculative report when repeated by vested interests in the media at prime time or on front pages of national dailies, instantly becomes an 'impending food disaster waiting to explode'.

Naturally, all this panic leads to hoarding by the 'common man'. People hoard in anticipation of shortages and not when there is an actual shortage. It is this hoarding by the common man which generates artificial demand at the aggregate level leading to increase in the prices of a commodity.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

If UPA government tackles inflation, it will collapse!

Once the necessary threshold level of panic is created, the rest is easy. Rumours, black marketeers and hoarders at the retail level then take over and ensure a cataclysmic price rise.

In India, with underdeveloped spot markets and poor infrastructure, it is easy to create demand supply gaps easily through this process of triggering panic by using the media.

Financial investors and their partners in investment -- the media -- act in tandem to create this panic. After all, they have taken positions in the futures market quite early knowing pretty well that it is they who have the ability to hype the failure of monsoon, leverage it and profit from it.

Commenting on this issue of over-hyping the failure of the monsoon in 2009, the Economic Survey for 2009-10 was particularly critical of the government's failure in not being able to check the 'hype' over the failure of the Kharif crop.

The survey further notes that this hype 'may have exacerbated inflationary expectations, encouraging hoarding and resulting in a higher inflation in food items'.

What is lost in this debate of the absurd is that the government allowed such speculation in the first place and then kept quiet when the players hyped up the future monsoon failure.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

If UPA government tackles inflation, it will collapse!

But that is not all. Some analysts argue that whatever be the impact of such 'intervention' by speculators, the consequences would be purely temporary and prices would return to normal so as to reflect the fundamentals.

That is, provided the fundamentals themselves are not subject to such intervention. But the more important question is what if sections of the government are beneficiaries of all this in the first place?

The answer to this question is simply fascinating. The Economic Survey 2009-10 points to the fact that the buffer stock of rice and wheat maintained in January 2010 was 12 million tonnes higher than the buffer stock of January 2009. In short, in a 'drought year' the government actually procured 12 million tonnes (subsequently allowed to even rot) from the markets when conventional economics suggests otherwise.

Surely, this classical case of 'hoarding by the government' would point an accusatory finger at someone within its ranks.

If inflation globally is caused by speculator pull and media push, inflation in India is witness to a peculiar local phenomenon -- administrative push and ministerial pull! Sadly, no economic textbook has a solution to this paradigm.

PS: The moral of this immoral story is that to tackle inflation the government needs to close down the commodity exchanges. But if it attempts to do it, the United Progressive Alliance government will collapse.

M R Venkatesh is a Chennai-based chartered accountant. He can be contacted at mrv@mrv1000@rediffmail.com