Photographs: Reuters Praful Bidwai

The ghastly violence and arson at the Maruti Suzuki India Ltd (MSIL) car factory at Manesar near Guragon in Haryana, which led to the death of a manager, undoubtedly marks a new low in industrial relations in India. It must be condemned strongly, unequivocally and without ifs and buts. There can be no justification for breaking human resources manager Awanish K Dev's legs. Immobilised, he was asphyxiated by toxic smoke when parts of the plant were set on fire.

The MSIL management has imposed a lockout and is busy demonising all its workers as criminally irresponsible and violence-prone. It wants to sack about a third of the 1,000 permanent workers and half the 2,000 contract workers, and replace them with new recruits. It has mounted enormous pressure on the Haryana government to arrest as many workers as possible and guarantee industrial peace, failing which it could threaten to pull out of Haryana.

The management's reaction, most Indian employers' response, and much media coverage of the issue, is excessive or biased. The Manesar factory has a history of labour unrest, but none of violence until July 18.

It defies credulity that more than 1,000 workers indulged in violence. That number exceeds the strength of an entire shift. It takes only a handful to start a riot once tempers rise. Sacking people en masse for the action of a minority reeks of "collective punishment", which is illegal and morally repugnant.

By all accounts, the trouble started on the 18th morning when a supervisor hurled casteist abuse at a Dalit worker. Strong protests broke out. Yet, there were negotiations between the recognised Maruti Suzuki Workers' Union and the management. The workers were enraged when the abused worker was suspended, but contrary to normal practice, no action was taken against the supervisor.

Click on NEXT for more...

Lessons from the Maruti violence

Image: Police and private security guards walk past a damaged reception block of Maruti Suzuki's plant in Manesar.Photographs: Ahmad Masood/Reuters

MSWU claims that to quell the so-far-peaceful protest, the management sent in hundreds of bouncers, who are on its payroll, to thrash the workers, who then retaliated blindly with whatever they could find, including tools and car parts. Hence the extreme, indiscriminate violence.

Outlook magazine has confirmed the bouncers' presence. MSWU blames the management for causing and aggravating the violence. According to many witnesses, more workers were injured than managers.

Nobody has convincingly refuted this account. It's not as odd as it might seem. Employing bouncers and goons is a regular, routine or standard management practice in the Gurgaon-Manesar-Dharuhera industrial belt. They are used to suppress the airing of grievances, intimidate workers, break strikes, physically attack union activists and undermine legitimate trade unions.

This broad pattern prevails in factories such as Omax Auto, Anchal Engineering, Speedomax and Honda Motorcycles and Scooters Ltd, besides Maruti-Suzuki. This has been documented not by some irresponsible ultra-radical activists, but by legal bodies like the Congress party-led Indian National Trade Union Congress, and the mainstream Communist party-led All-India Trade Union Congress and Centre for Indian Trade Unions, and confirmed by independent fact-finding teams.

It is extremely difficult to establish the use of bouncers conclusively in the specific case of MSIL because no worker or white-collar employee wants to talk. More than 110 workers, including young apprentices and interns, have been rounded up by Haryana's notoriously brutal police, and each has been charged with murder or attempt to murder. Such charges wouldn't stand scrutiny in most cases, but they serve the purpose of denying bail to the accused and terrorising them.

Click on NEXT for more...

Lessons from the Maruti violence

Image: Workers assemble a car at a Maruti Suzuki plant in Manesar.Photographs: Danish Ismail/Reuters

Most of MSIL's 3,000 workers have gone underground in legitimate fear of detention, beatings, and even torture as the police have unleashed a reign of terror in the area, harassing workers' relatives or acquaintances who aren't even remotely connected with the violence. The operational principle here too is the obnoxious practice of "collective punishment".

The Haryana police by all accounts has become even more trigger-happy than usual under the pressure of its political bosses who are only too eager to please the Maruti-Suzuki management. There is no such thing as the rule of law in Gurgaon-Manesar. A citizen has no protection from the predatory agencies of the state. Might, or rather, brute force, rules in Haryana's industrial belt.

Workers' discontent and unrest at MSIL and must be understood against the backdrop of callous management practices, including back-breaking workloads which were recently further intensified, rampant employment of contract labour on low wages, refusal to negotiate better wages and working conditions and reduce gaping wage disparities, and the imposition of company trade unions and prolonged non-recognition of the unions chosen by the workers.

The MSIL workers are subjected to a harsh shop-floor discipline to produce a car every 50 seconds. The situation resembles the oppressive conditions of super-mechanised production immortalised in Charlie Chaplin's film "Modern Times".

MSIL workers must labour hard for eight hours at a stretch, except for two 7.5-minute toilet breaks and a 30-minute lunch break. Both the canteen and the toilets are half-a-kilometre away. No wonder there is "unbearable tension" in the factory.

Click on NEXT for more...

Lessons from the Maruti violence

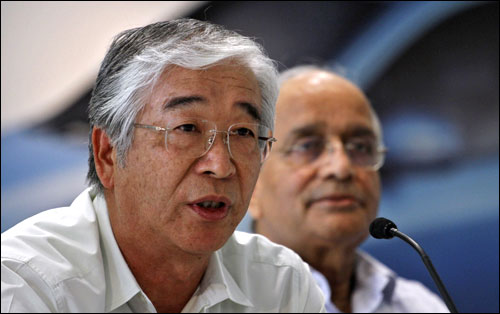

Image: Maruti Suzuki India's MD and CEO Shinzo Nakanishi (L) speaks, beside Chairman R C Bhargava during a news conference in New Delhi on July 21, 2012.Photographs: Parivartan Sharma/Reuters

The Suzuki management has taken the cult of compulsory attendance, obsessive punctuality and relentless search for productivity to new extremes Work has been speeded up to ultra-stressful levels, and is measured in "actions per minute". Both workers and managers complain of high mental stress and rude behaviour by their superiors, who are tasked to extract as much work as possible from employees. Thanks to this, slain HR manager Dev wanted to quit the company.

Workers are discouraged from taking leave. They get just nine days' leave in a year, besides the weekly off. For every day missed beyond the nine sanctioned days, Rs 1,500 is deducted from their wages. If they turn up even one minute after the shift begins, they lose half-a-day's wages. Their grievances are usually ignored.

Supervisors are routinely rude, and allegedly, often violent. The consultancy Karvy Stock Broking holds that the real issues at dispute at the Manesar plant are "more psychological" than "materialistic".

But MSIL scores poorly on "materialistic" issues too. Most of its workers live in unhygienic, indeed inhuman, conditions in hovels where four men share a tiny room and 30 men a filthy toilet Not only are two-thirds of MSIL workers on contract; they get paid less than one-half of what the permanent workers earn - although they do the same work and are needed around the year. This, as former Union labour secretary Sudha Pillai says, violates the principle of equal pay for equal work.

The management insists the contract labour issue is non-negotiable. But unionists know that the key to their strength lies in solidarity between the permanent and contract workers. Other issues like wages and union recognition have often proved intractable at the MSIL factory. Nothing could be a better recipe for bad faith and strife. All this has turned the factory into a tinderbox.

Lessons from the Maruti violence

Image: Officials stand in front of a damaged doorway inside the premises of Maruti Suzuki's plant in Manesar.Photographs: Ahmad Masood/Reuters

Little surprise that MSIL has witnessed two strikes in the last 13 months. A two-week strike last October was over the management's non-registration of the workers' preferred union. The state government intervened and a tripartite agreement was arrived at. The union says the management is trying to wriggle out of this with the complaint that it was forced to hire political appointees. It has refused to negotiate in good faith the union's charter of demands submitted in April.

The Suzuki management has shown great cultural insensitivity towards the workers - for instance, over customs like Vishwakarma Puja, when workers worship the machines they work with. In an unusually harsh (for a Japanese official) public statement, Tamaki Tsukuda, minister (economic) in the Japanese embassy, says: "The management did not quite know how to deal with a new band of people representing the workers"; it wasn't aware of the pent-up emotions among the workers.

Violence at the Maruti-Suzuki plant marks a watershed. However, similar, if somewhat less volatile, conditions exist in many other industrial corridors in India amidst escalating employer-labour tensions. There is growing frustration among workers at a decline in their real wages over 15 years, rising job insecurity, and non-payment of dues. Wages' share in manufacturing value addition has dropped from 30 per cent to under 12 per cent over 30 years, while the share of profits has more than doubled from 23 to 56 per cent.

Click on NEXT for more...

Lessons from the Maruti violence

Image: Police and firefighters are seen at the Maruti Suzuki's plant after the clash.Photographs: Reuters

This should prompt serious rethinking about and reform of industrial relations in India. What we need is a high-powered commission comprising labour studies scholars, sociologists, jurists, unionists, enlightened managers, and administrators and policemen of impeccable integrity.

First, it should investigate what happened at Manesar, based on forensic evidence and testimonies of witnesses protected against identification, intimidation and harassment, unlike the victims of Gujarat's communal carnage of 2002, who became vulnerable to pressure and allurement.

Secondly, the commission should look into India's vitiated industrial relations climate, its causes, and ways of remedying the situation. Under a new industrial relations deal, the worker's basic right to a living wage and decent working conditions, as well as the right of association and collective bargaining, must be respected and made effective, while the pernicious practice of contract labour employment must be abolished.

article