Known as the investor with "the Midas Touch", Buffet is the most successful investor alive - the only member among the Forbes' list of the world's richest to have earned his fortune entirely through investing. Every investor can profit from how Buffett invests...

The market and fair value

Of all Buffett's ideas perhaps the simplest and most important for a non-professional individual investor to grasp is just this: value will in time be reflected in market price. (It certainly is not so reflected continuously.)

It's just a question of time, and not always very much time. Most investors don't have the profound feeling professionals acquire that market anomalies are perforce ephemeral.

It's just a question of time, and not always very much time. Most investors don't have the profound feeling professionals acquire that market anomalies are perforce ephemeral.

If a bond is selling out of line with other bonds of similar tenor and quality, it will move to its correct value in time.

If a stock that really does represent a dollar's worth of solid assets is selling for 60 cents, it will, sooner or later, not only go back to a dollar but quite likely more than a dollar.

Prices of stocks, and of the market as a whole, in time not only reflect fair value but sooner or later excessive valuation.

Further, it's improbable that from the low point this recognition will take more than a few years, and it's likely that the period will in fact be about three. In studying the records of great investors, I've often been struck by this three-year phenomenon. What's the reason?

Good investment is quantified fussiness: when you buy, you want to hold out for the lowest price you really can buy for, and when you sell, you want to hold out for the highest price you really can receive.

There are dozens of criteria for bargains and for excess prices. If they work, you'll find yourself buying around the bottom of the usual four-year market cycle, and selling near the peak about three years later, before the dive in the fourth year.

So by the nature of that cycle, it would be surprising if a really good buy - presumably bought near the lows of the cycle - would not show a good profit later in the same cycle.

(Of course, if you buy before the low, then it could take an extra year, or even two.)

This was not always so. Some years ago, most trading was done by the public, there were relatively few mutual funds, and security analysis was done by hand on accounting spreadsheets, the computer and such not being available.

Under those circumstances it was theoretically possible - although unlikely - for a bargain to go unperceived for years. Not that this was Graham's experience.

Today, however, with analysts constantly combing their database for bargains, like an airport tower searching the skies with radar, a bargain rarely continues unperceived for long, so in the effervescence of a market boom, it is almost certain to have its move.

There are some ways of improving on this procedure. One is to try to wait until the relative performance of a given stock to the whole market shows that it is no longer collapsing but is beginning to find support from courageous buyers. If you are not a large institution, this approach can save you money. If you are an institution, then it's better to buy right into the weakness.

Another, practiced by, among others, Robert Wilson, for years a highly aggressive and successful speculator, consists of taking a large position and then talking about it to all and sundry - preferably Wall Street columnists.

Profiting from disasters

The stock market reacts in a manic-depressive way to news, and when disillusionment strikes, things will probably go too far the other way. That, in turn, may create the very opportunity that the skillful investor waits for.

If a stock, fallen from favor, is now selling at $100 a share, and a piece of very bad news should push it down to $90, the chances are good that it will in fact drop to $80 or $70, thus creating a buying opportunity. Sometimes, it will even go to $60 or $50.

One of Buffett's purchases that people still talk about was when the 1963 Tino de Angelis salad oil scandal hit American Express. Briefly, an American Express subsidiary found itself possibly liable for hundreds of millions of dollars of damage claims arising from the sale of salad oil that did not exist, and the stock dropped sharply in the market.

Buffett was able to establish that the "franchise" value of the company's basic business, notably its credit card and the traveler's checks with their huge "float" were intact.

When you buy an American Express traveler's check, you in essence make the company a free loan in exchange for a piece of printed paper. The total of those free loans - the "float" - amounts to a couple of billion dollars at all times. Anyway, Buffett bought 5 per cent of American Express, and it paid off handsomely. The stock quintupled in five years.

More recent examples of disasters: the Bhopal explosion, which collapsed Union Carbide, giving the Bass Brothers a chance to make an immense profit in a matter of months as the stock rebounded almost to its old price; the Chrysler near-bankruptcy, which Magellan Fund cashed in on; Disney, during the gas lines; and the cigarette companies back in the 1970s, after they were banned from advertising on TV. The succeeding years produced enormous gains in their stock prices.

Most illogical of all, incidentally, is to sell on a war scare. The experienced investor does the opposite. Herbert Allen bought a mining company in the Philippines in 1942. War always means a debauching of the currency, as the country incurs huge deficits to finance the military buildup and then the fighting.

As the currency fades away, investors flee to things, including things represented by stocks. The things themselves are denominated in larger and larger numbers of depreciating currency units. So in fact one should sell bonds and buy stocks on a war scare, particularly if the scare pushes stock prices down, as it usually does.

[Excerpted from the book, The Midas Touch: The Strategies that Have Made Warren Buffett the World's Most Successful Investor. Published by Vision Books.]

(C) All rights reserved.

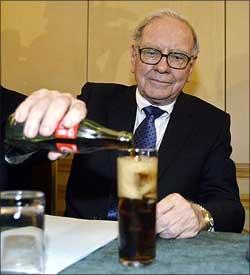

Image: Warren Buffett fills a glass with Coke during a news conference in Madrid. | Photographs: Andrea Comas/Reuters