Australia's deficiencies were exposed

Daniel Laidlaw

On previous Australian tours of India, there have always been excuses that

could be called upon to explain away the poor results. In 1996, Australia

was without Shane Warne in a one-off Test played on a dodgy wicket. In 1998,

there was Warne's shoulder injury and the absence of spearhead Glenn

McGrath. But on the 2001 tour, there was not a single extenuating factor in

Australia's performance. The series loss cannot be attributed to anything

other than Australia's deficiencies, exposed by India's superior cricket.

Entering the tour, the Australians were fully aware of what to expect. They

had planned for the series for a year, had been there before, and were

familiar with the types of challenges playing India at home presented. In

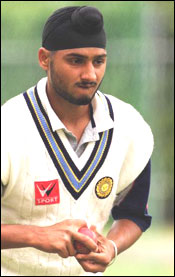

hindsight there are undoubtedly things it would do differently, like analyse

Harbhajan Singh's strengths in more detail and revise its approach to him

accordingly, but beforehand its preparation could not have been better.

Despite this, it still failed.

Entering the tour, the Australians were fully aware of what to expect. They

had planned for the series for a year, had been there before, and were

familiar with the types of challenges playing India at home presented. In

hindsight there are undoubtedly things it would do differently, like analyse

Harbhajan Singh's strengths in more detail and revise its approach to him

accordingly, but beforehand its preparation could not have been better.

Despite this, it still failed.

One redeeming aspect of the tour and source of comfort for Steve Waugh's men

is that they lost on their own terms. They had a plan in mind, and with the

confidence of 16 consecutive wins behind them, the belief to execute it. It

was a good plan, too, and effective for a time. The problem was that it was

undermined by batsmen who were found technically and temperamentally lacking

when the opportunity arose to first keep India at bay in the second Test

then put them away after a great start in the third. The commitment to the

cause couldn't be questioned, however, and they went down fighting. The

captain claimed he was proud of the effort and that his team should be

judged on the way it played, rather than the actual result.

Why, then, was Australia found wanting? The Aussie juggernaut had compiled

the oft-mentioned 16-Test victory sequence, extended it to 17, and was

stopped dead in its tracks virtually as it was planting its flag to claim

the last frontier. Where did the ambush come from? Should it have been so

surprising? If you look closely, there were warning signs to indicate it

might occur from the beginning of the tour. From the opening tour match

against India 'A', the batting had shown a propensity to collapse and the

bowling a worrying inability to make an impression.

Australia was able to lift itself in the first Test but even then achieved

victory by moving in swiftly for a quick kill, rather than engaging in a

lengthy fight. Better suited to the conditions, a long battle favoured

India, and Australia's batting wouldn't have been able to sustain it.

The principles around which Australia planned to win the series were bold

and commendable. There was to be no room for wondering what might have been.

The clearly stated strategy was to go for the jugular by attacking the

Indians with pace bowling, then pressurise an inexperienced spin attack by

smashing it from the outset. Instead of batting with its usual aggression,

Australia actually lifted it a notch and pursued the bowling more

thunderously than ever. It was a worthwhile method on the comparatively

small Indian grounds with lightning outfields, but too few were able to

execute the high-risk/high-reward approach. It had to be supported with

solid defence but many of the batsmen could not assuredly play quality spin

defensively for long periods. Harbhajan's straight ball or top spinner

consistently deceived the Aussies.

The principles around which Australia planned to win the series were bold

and commendable. There was to be no room for wondering what might have been.

The clearly stated strategy was to go for the jugular by attacking the

Indians with pace bowling, then pressurise an inexperienced spin attack by

smashing it from the outset. Instead of batting with its usual aggression,

Australia actually lifted it a notch and pursued the bowling more

thunderously than ever. It was a worthwhile method on the comparatively

small Indian grounds with lightning outfields, but too few were able to

execute the high-risk/high-reward approach. It had to be supported with

solid defence but many of the batsmen could not assuredly play quality spin

defensively for long periods. Harbhajan's straight ball or top spinner

consistently deceived the Aussies.

The series exposed flaws in Australia's game that had been hidden against

lesser opposition. An inconsistent top order that often relied on Gilchrist

and the tail to rescue it from trouble before watching the bowlers blast

away the opposition for less than 300 found that reasonable totals achieved

in such precarious fashion were not enough. Against a batting team with the

ability to match Australia with a total of more than 350, the batsmen had

the responsibility of contributing more than they were usually required to

provide, and were unable to fulfil it.

The sad part is the lack of heavy runs from the top seven came at a time

when Australia had a batsman in Hayden having the best series of his short

and hitherto modest Test career. Hayden was one of the least expected to

have a significant impact on the series and Australia wasted his exceptional

production at the top of the order. Hayden's form should have been just the

bonus required to tilt the series in Australia's favour.

There was a significant chasm between Australia's best players and its next

tier of performers. Glenn McGrath and Jason Gillespie both bowled

magnificently. McGrath took 17 wickets while 'Dizzy' deserved more than his

13. To bowl as well as they did took enormous discipline, stamina and

persistence. Their control was immaculate. It had to be. Despite bowling as

well as Australia could possibly have hoped their efforts merely put the

tourists on even terms, at best. The difference in class between that pair

and the rest of the attack was immense.

Without the same level of pace and control, Damien Fleming was reduced to

bowling quick off-spinners by the second innings of the first Test. Michael

Kasprowicz was tried in the second Test but couldn't match McGrath and

Gillespie's persistently challenging line and length. On grounds where

anything loose was easily dispatched to the boundary, near perfection was

required. The pitches gave the quick bowlers nothing so every success had to

manufactured through sheer effort and continued toil.

Regardless of the virtual perfection necessary from the fast bowlers to

maintain pressure, it was still preferable to relying on spin to get the

majority of the wickets. That would have been utterly futile, as evinced by

the ease with which Warne was played.

In a losing series the success stories were few, but the ones who did

succeed did so spectacularly. Matthew Hayden finally arrived as a Test

batsman and will probably be the first player picked for the Ashes tour.

Glenn McGrath proved his champion qualities again, flourishing in a

traditional fast bowler's graveyard. He could not be attacked without risk.

Jason Gillespie, for so long a great talent ruined by injury and bad luck,

made it through a physically and mentally demanding series without breaking

down, all the while bowling with typical intensity. If he stays healthy,

he's a certainty to take 300 wickets.

In a team that prides itself on unity, working together and not relying on

the next bloke to do the hard work, it is damning that there was such a vast

difference between those who can be pleased with their tours and those who

will go home disappointed. Normally, Australia has an even spread of contributors, with everyone standing up to make an impact on the series at

some point. In India, that didn't happen, and the margin between the

productive and the mediocre was too wide to be overcome.

Overall, although it was hopefully an educational experience for some

players and a series that in future they can proudly claim to have been

involved in, Australia's standing was diminished by the tour. They came as

world champions with a point to prove and left with pride intact, but

mission unaccomplished. A series victory in India now becomes a slighter

bigger bogey for the next Aussie touring side to face. At least they will

have gained a little more accumulated knowledge from coming desperately

close the last time.

You can also read:

Disaster spelt India's comeback

Series Overview: Australia | India

Mail Daniel Laidlaw