Ground realities

Daniel Laidlaw

One day, international cricket will become a sport that can last a series or

tournament without some form of controversy or discontent confined directly

to the matches being played. It has to happen eventually. Doesn't it?

For the time being, the game lurches from one problem to the next but, more

disappointingly and in what is an indictment of those who govern it,

frequently treads over old ground and scandals. Most of the issues like

umpiring, dissent, throwing and even corruption are in no way original

problems. Pitch invasions by spectators are just the latest example.

England has a crowd control problem. Shambolic scenes have again been

witnessed in matches involving Pakistan in England. It cannot, or at least

definitely should not, be surprising to anyone. Measures were supposed to be

in place to prevent it prior to the NatWest series. After they failed

dismally in the opening match at Edgbaston, the England Cricket Board

revealed it was taking the issue "extremely seriously" and introduced a

range of superficial initiatives that were supposed to combat the problem.

Those measures failed utterly at Headingley, when a second premature

invasion prompted England captain Alec Stewart to forfeit the match, and

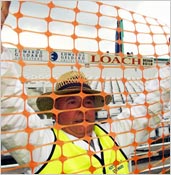

again were little more than cosmetic at Trent Bridge on Tuesday when flimsy

plastic fencing at least held the crowd back until after the game had been

completed.

Those measures failed utterly at Headingley, when a second premature

invasion prompted England captain Alec Stewart to forfeit the match, and

again were little more than cosmetic at Trent Bridge on Tuesday when flimsy

plastic fencing at least held the crowd back until after the game had been

completed.

After the second pitch invasion at Headingley, in which a steward was injured, there was an identical reaction from the ECB. In a disturbing sense

of déjà vu, they announced security would be improved and that they were

"extremely concerned" by the epidemic.

If it was possible to introduce more security after the trouble at

Headingley, why was it not already in place? One would think that, realising

the seriousness of the issue for the players, the ECB would have done

everything it possibly could to prevent invasions occurring again

immediately after the scenes at Edgbaston. It is an indictment of the Board

that it had greater security measures available to it and yet evidently was

not prepared to introduce them. Why weren't they already in place?

Moreover, why haven't they been in place for two years? This is far from

being a new crisis, even in England. At the 1999 World Cup, matches also

suffered from unsafe ground invasions and the ECB did nothing. Australian

captain Steve Waugh's warnings that player security was insufficient went

unheeded then, and he is still making the same statements now, echoed by

Alec Stewart and Waqar Younis.

Until this series, the attitude the ECB has portrayed is one of "it's in our

culture, old chap, and if you don't like it then get off the field quicker."

Never mind the rights of the players to feel safe in their work environment.

The alternative is to simply refuse to play, a stance the confrontational

Australians are not averse to taking.

A second forfeit nearly occurred at Trent Bridge, although for a different

kind of security breach. Steve Waugh has made his feelings on the issue of

player safety known for years, strenuously arguing that not enough was being

done to protect them. It came as no surprise whatsoever, then, when the

Australians walked off in protest on Tuesday after a firework was thrown

near Brett Lee on the boundary. When Steve Waugh makes a threat he is good

to his word, so player power ruled.

A second forfeit nearly occurred at Trent Bridge, although for a different

kind of security breach. Steve Waugh has made his feelings on the issue of

player safety known for years, strenuously arguing that not enough was being

done to protect them. It came as no surprise whatsoever, then, when the

Australians walked off in protest on Tuesday after a firework was thrown

near Brett Lee on the boundary. When Steve Waugh makes a threat he is good

to his word, so player power ruled.

It was evidently made clear that if player safety is jeopardised again,

there would be no match. In isolation one firecracker may seem like a

trivial event to spark a walk-off, but the Australians have experienced

similar incidents before on numerous occasions and their hardline stance is

to be commended. If the authorities cannot safeguard cricketers on the field

then at least they can look after their own welfare. The ECB cannot say they

had not been warned.

The latest innovation, plastic fencing, saw its first action at the end of

the game and worked marvellously - for a few seconds. Although it allowed

the players a few extra seconds to reach safety, as a defence of the ground

it was ultimately useless and only served to dangerously incite the

invaders.

The most frustrating part of the entire issue is the apparent stubbornness

of the ECB in refusing to solve it, as it really should not be that

difficult to stop once they decide to face the issue directly. After all,

pitch invasions on the scale witnessed in England do no not occur in the

majority of Test-playing nations. Australia, South Africa, India and

Pakistan each have, to greater or lesser degrees, effective methods of

keeping spectators off the ground and ensuring the safety of players.

At present, the ECB are seeking to treat the symptoms rather than the cause.

It seems they do not want to face the fact that a tradition that allows for

spectators to pour onto the arena for post-match presentations is unworkable

in a modern sporting environment, with volatile capacity one-day crowds from

differing cultural backgrounds.

If it wants to permanently solve the issue, the ECB has to take the most

logical and obvious step and announce that due to the patently unsafe invasions,

the tradition of spectators entering the playing arena is henceforth

prohibited. If it requires government legislation, then so be it. That law

must then be backed up with prosecution and heavy fines, possibly in

conjunction with bans from the ground, for any who violate it.

Alternatively, they could just keep incrementally increasing the number of stewards following each invasion, continuing to declare how seriously they

are viewing the problem while the ugly scenes are repeated ad nauseam...

More Columns

Mail Daniel Laidlaw