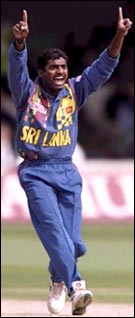

The Murali Phenomenon

Daniel Laidlaw

He is currently ranked as the No. 1 bowler in the world and is arguably one

of the greatest of all time. He has ten 10-wicket hauls, more than anyone

else, and at 29 years of age has recently become the youngest bowler to

reach 400 Test wickets, in eight fewer matches than the next fastest.

Muttiah Muralitharan is simply a phenomenon, a bowler of astonishing

statistics who, in terms of publicity, still appears to be under-appreciated

outside of Sri Lanka given his stature in the game.

Muralitharan, one of a kind, has surely re-defined off-spin. His action is

controversially unique and before long his record-breaking achievements will

be, too. The cricket world had better come to terms with Muttiah

Muralitharan one way or another for this bowler is going to leave an

indelible mark on the record books whether he is widely appreciated or not.

It's becoming impossible to ignore him.

Currently, Murali is not only the best spinner in the world but, as

evidenced by the PwC ratings, the best bowler in the world, period. He will

more than likely overtake Shane Warne (430 wickets), the first spinner to

pass the 400-wicket milestone, as the first to surpass Courtney Walsh's

landmark of 519 Test wickets.

For a bowler defined by his statistics, it is interesting that Muralitharan's abnormal action remains the most discussed feature of his game. The

freakish wristwork that generates the turn of a leg-spinner from the

bent-elbow delivery of an off-spinner remains contentious and has seen him

called for throwing in three separate matches. It is a stigma impossible to

avoid yet one Murali has seemingly taken in his stride.

It is inevitable that Muralitharan should be compared to the era's other

great spinner, Shane Warne. Warne is credited with single-handedly reviving

the art of leg-spin and for all his character flaws has undoubtedly been a

positive influence on world cricket. Muralitharan's impact on the game is

more difficult to assess. One gets the impression he is still regarded as

more of a curiosity than celebrated figure, a freak of nature whose record

is respected and marvelled at but for whom any praise is reserved. That

deserves to change.

It is inevitable that Muralitharan should be compared to the era's other

great spinner, Shane Warne. Warne is credited with single-handedly reviving

the art of leg-spin and for all his character flaws has undoubtedly been a

positive influence on world cricket. Muralitharan's impact on the game is

more difficult to assess. One gets the impression he is still regarded as

more of a curiosity than celebrated figure, a freak of nature whose record

is respected and marvelled at but for whom any praise is reserved. That

deserves to change.

To the naked eye, Murali's action is definitely dubious, as are claims that

he has been cleared of throwing by the ICC, as if this prevents any bowler

from subsequently throwing a delivery in the future. However, if scientific

tests have proven that, using his normal action, his elbow does not

straighten in delivery, then it has to be accepted until proven otherwise.

He is a bowler too remarkable to be relatively ignored.

To put Muralitharan's ten 10-wicket hauls into some kind of context, spin

rival Warne has five, while Walsh only claimed three. Before being first

called for throwing in December '95, Muralitharan had played 22 Tests for 80

wickets at 32.76. Since that time, he has played 49 for 323 at 20.93.

Discounting matches against Zimbabwe and Bangladesh, Murali still has 321

wickets at around 25. At home, he has 260 wickets at 21.14, while his away

record reads 144 at 27.85. It is a record which has not been achieved

against weak teams on turning home pitches alone.

Clearly, Muralitharan is Sri Lanka's most valuable asset and often their

lone match-winner, the bowler on whom their fortunes heavily depend. An

indication of this is Sri Lanka's 8-match home winning streak against

Bangladesh, India, West Indies and Zimbabwe, during which Murali has taken

75 wickets.

As the bowler who carries Sri Lanka's attack, it is debatable whether this

dependency makes his feats more difficult to achieve, or if being the sole

match winner provides him more opportunities to take wickets. In Murali's

case, it is more likely the latter. It is not as though Chaminda Vaas, a

fine bowler in his own right, and company are so bad that Muralitharan

receives no support. Rather, Muralitharan is surrounded by a competent

attack that can build and sustain pressure, to which he lends the incisive

edge.

Although there is probably less stress on his body because he is an

off-spinner, Muralitharan's greatest danger that, like Warne, he will

eventually suffer from over-bowling. Murali bowled more overs than any other

bowler in the world last year and as Sri Lanka's undoubted trump, this is

unlikely to change, especially at home.

Looking at Sri Lanka's scorecards,

it is routine to see him bowl 40 overs in an innings, and even for a fit an

injury-free player, this workload will eventually wear him down. However, at

the rate he's going, he may have at least 600 wickets before it happens.

In the immediate future, Muralitharan is likely to be judged on his away

performances in generally unfavourable conditions in England, Australia and

South Africa, where having quality fast bowlers operating at the opposite

end will be crucial to both his and Sri Lanka's success.

Coach Dav Whatmore

deserves great credit in this regard, as he has recognised the need to

develop fast bowling talent to win consistently overseas, in addition to

having the spinning strength of Murali to dominate at home.

Although they have smashed opposition little more than mediocre recently,

Sri Lanka have nevertheless been impressive, and their coming tours will be

essential to gauging their true standing. With Pakistan yet to translate its

talent into results, India still woefully inconsistent and Bangladesh in its

infancy, Sri Lanka could be quietly emerging as the best team on the

subcontinent. And it is Muttiah Muralitharan who has carried them there.

More Columns

Mail Daniel Laidlaw