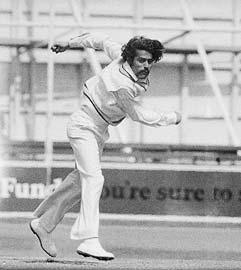

For a generation brought up on cable television, Bhagwat Chandrasekhar's legend comes to life only in black and white photographs.

The pictures, gone slightly yellow with time, show a tall, lean bearded man, dust kicking at his feet and a mop of hair pulling behind, as he completes bowling yet another unreadable delivery; the aggression in his eyes masks the geniality of the man.

But the real story lies in the full-sleeves shirt, buttoned at the wrist, which veils a polio-withered right arm.

But the real story lies in the full-sleeves shirt, buttoned at the wrist, which veils a polio-withered right arm.

In many ways we go looking for it, picture after picture, trying to make sense how such a glaring handicap became his most potent weapon. It works, because it is a staggering tale of courage and defiance.

Chandrasekhar was struck with the disease when he was five, but he took up the game, first bowling with his good hand, then switching on to the right hand because it could impart more revolutions on the ball.

Making his debut for India at the age of 19 against England in 1964, at the Brabourne stadium in Mumbai which came to be his favourite hunting ground, Chandrasekhar quickly became an integral part of the Indian team.

In his second season, he was able to scalp 18 West Indies wickets in three Tests and followed it up with 16 against England in England in 1967.

India, feeling the pinch of lack of quality fast bowlers, had found a wicket-taker in Chandra. His fastish leg-spinners, which many vouched could be faster than India's frontline bowlers, were almost impossible to read. Despite being a leg-spinner, the leg-break wasn't his stock ball. Chandrasekhar bowled so many googlies and flippers that batsmen were caught napping when the leg-break whirred in.

In an earlier interview with rediff.com, he broke down his art: "I had a different grip, like a seam bowler's with my fingers spread across, so I could get bounce off the deadest pitch. I didn't do too much thinking."

"I couldn't flight the ball. I was more a fast bowler, really, everything I bowled was fast -- my top spinner, googly, flipper, everything. It was like asking (Dennis) Lillee to flight the ball."

Had it not been for poor fielding by India in England in the 1967 series, the bowler would have returned with better figures. The team also could have avoided the 3-0 white wash.

Misfortune was still to follow this soft-spoken man from Mysore. During the off-season he met with a scooter accident and lost out on crucial years.

The resurgence though proved to be better than the first coming.

It was the summer of 1971 that defined him. It was India's seventh visit to England. All the previous occasions had been unremarkable. This looked to be no different. England had just acquired the Ashes in Australia, and under Ray Illingworth were speculated to be the best team in the world. But India had nothing to lose.

They started their campaign on a high, losing only one of the ten warm-up games (against Essex). The team was gelling well under Ajit Wadekar and did well fight out draws in the first two Tests.

The third and final dawned on August 19. England piled up 355 runs in the first innings; India ran out of gas on 284 after the second day was washed out.

The home team hardly looked in trouble, till Chandrasekhar struck. In the most fabled spell of 6 for 38 in 18.1 overs, the leg-spinner scripted one of India's most decisive moments in world cricket as India won by four wickets.

His assessment: "On that day I was always unplayable.

"It was a vital match for me, because if I didn't do well, it was likely I wouldn't play Test cricket again.

"I didn't think about the batsmen in that innings; I concentrated on getting my rhythm right. I had four fielders around the bat and that is all I wanted. Eknath Solkar at short leg, Ajit Wadekar at slip, Abid Ali/S Venkataraghvan at leg slip, that is all I really needed -- the others were there to stop the ball reaching the boundary if I bowled a bad ball.

"The first wicket I got was John Edrich, with a faster one that went through him before he even got his bat down.

"Keith Fletcher walked in looking very nervous, and he didn't survive too long; Solkar got him with a superb catch at forward short leg. The next two wickets fell to mistimed shots. Then Venkat took a superb catch to get Luckhurst.

"Keith Fletcher walked in looking very nervous, and he didn't survive too long; Solkar got him with a superb catch at forward short leg. The next two wickets fell to mistimed shots. Then Venkat took a superb catch to get Luckhurst.

"Wadekar then got (Bishen Singh) Bedi into the attack -- it wasn't like I was tired or something, but anyway, Bedi got the breakthrough when he deceived Derek Underwood in flight and had him caught by Ashok Mankad. The last wicket was Price. I was bowling, I kept it in the same spot and then bowled a googly, that was it."

India's reluctant hero had finally found the spotlight.

The next year, when India faced England at the Ferozshah Kotla in New Delhi, Chandra bowled another mesmerising spell. India lost the match despite him returning figures of 8 for 79 in the first innings, his best in a 16-year Test career.

Chandrasekhar, part of the famous Indian spin quartet that included Bedi, Venkataraghavan and E A S Prasanna, was India's biggest match-winning bowler till then. An attacking bowler by instinct, he liked to experiment to the extent that the captain had to take him off the attack to curb his enthusiasm.

His penchant for taking big wickets showed in the fact that he made a bunny out of one of the heaviest scorers of the time -- West Indies captain Clive Lloyd. Alan Knott, the England wicketkeeper, and Keith Fletcher were also his pet batsmen.

The shy bowler however proved to be a time-tested number eleven batsman.

At one time his name was entered in the batting records for the most number of ducks -- 23. He also got four pairs in Test cricket, but has since passed on the mantle of the softest batsmen.

Chandrasekhar, who registered double-figures only on five occasions in 58 Tests, was presented a bat with a hole in the blade as a symbolic representation of his bat. Not oblivious to his batting talent, the bowler accepted it with hearty laughter.

His batting may not have been anything to write home about, but his biggest contribution came by way of his wickets away from home.

The win at Oval in 1971 was the most significant, but he boasts of the best away record by an Indian spinner.

In the 24 matches he played on foreign soil, Chandrasekhar scalped 100 wickets at an average of 32.

He finished his first-class career with over a thousand wickets, a feat achieved only by two other Indians -- Bedi and Venkatraghavan.

The time when India's spin bowlers came into their own were heady days for Indian cricket.

Consistent supremacy was still undone due to a fragile batting line-up and an almost non-existent fast bowling attack. It leaves room for speculation: If India had the fast bowlers to get the initial breakthroughs or have enough runs to play with, what dangers would bowlers like Chandra and Bedi have posed?

But Chandrasekhar never complained. He could be drawn to tears if India lost, but never gave up till they did. Motivating his teammates, many times by sheer example, putting in the effort on the field despite a useless arm, he won many friends. And admiration often swelled the camaraderie.

He has been referred to as a 'freak' bowler, but there was nothing freak about his success. An introvert did not become a colossus in Indian cricket by accident; an honest trier was merely rewarded for the effort.

Chandrasekhar turns 60 on Tuesday, May 17. It has been two decades since he held court on a cricket pitch, but the audience continues to savour his defiance. The tale has grown in layers, painted in golden hues, seen on celluloid, but the core of courage is so strong that the picture has hardly distorted with time.