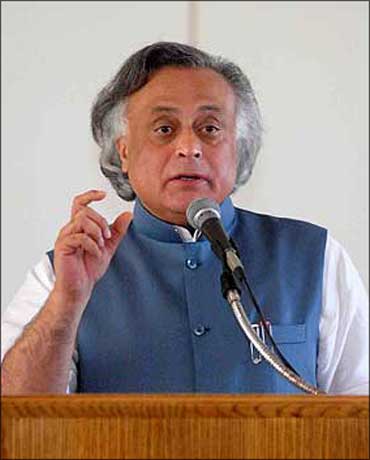

The decision of Union Minister for Environment and Forests Jairam Ramesh not to grant Stage II forest clearance to the proposal of the Orissa Mining Corporation (OMC) for bauxite mining in Niyamgiri in Orissa has been welcomed in many circles, in particular by the environmental activists, for the protection it will provide to an ecologically sensitive area of the country and to the Kondh tribes (and Dalits) living in the area.

There are, however a few disturbing questions that need to be answered by the ministry in order to buttress the minister's claim that the decision was an objective one with no prejudice or politics influencing it.

First, the manner and time-line followed in the decision-making. The Orissa state government seems to have applied for final clearance in August 2009.

The Forest Advisory Committee (FAC) has been deliberating the proposal at least since November 2009. In addition to the information submitted by the State and the central government's own agencies, it had the benefit of the recommendations made by a three-member expert group which submitted its report in February 2010.

FAC then asks for yet another committee under the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, which is the nodal agency in the central government for tribal rights. The environment minister, however, appoints his own committee (the Saxena Committee) in the last week of June 2010.

Then the pace quickens: The environment minister writes to the law ministry on July 19 to obtain the Attorney General's opinion if the ministry of environment and forests (MoEF) apply its mind and decide in the light of the Supreme Court's earlier decision giving forest clearance.

. . .

The AG replies promptly on the following day; Saxena submits report on August 16, FAC deliberates without much loss of time and submits recommendations on August 23, and the minister announces his decision with a 20-page reasoned order on August 24, 2010!

The must be a record in governmental working! The affected party, namely the Orissa government, is hardly given any chance to given an explanation to the MoEF.

In fact, the hapless Orissa officials seem to have met the minister on August 24 when he was in a tearing hurry to announce his decision!

Second, OMC's proposal for forest clearance for the Niyamgiri bauxite mines is separate and distinct from Vedanta Aluminium Ltd's (VAL) aluminum refinery project, although bauxite is meant for the refinery. Why have these two cases been mixed up in the minister's order?

Forest clearance is a statutory requirement under the Forest Conservation Act 1980 and the FAC was deliberating on the subject on the request made by OMC/Orissa government and the minister is within his rights to act on their recommendation.

If VAL violated the conditions of its approval or even the Environment Protection Act, it could have been proceeded against separately.

. . .

After all, the MoEF's eastern regional office had sent its communication reporting violations in May 2010. By combining the two issues the ministry gave the unfortunate impression that it was targetting Vedanta rather than dealing with forest clearance for Niyamgiri mines.

One of the major issues raised by the Saxena Committee and endorsed by the minister is the potential ecological and human costs of the mining project.

In fact, this is an issue which is relevant not so much during forest clearance procedure but more appropriately during the impact assessment study under the Environment Protection Act.

For Niyamgiri both 'in principle' forest clearance and environmental clearance had been given. Besides, the 'in principle' approval was given in October 2007, a month before the Supreme Court's order on the subject.

Did the MoEF discover the ecological and human costs only after receiving the Saxena Committee report?

The main thrust of the Saxena Committee report and about the only valid reason for denying final forest clearance for the Niyamgiri mines appears to be the alleged non-recognition of the forest rights of the tribals and absence of consent from the concerned communities for diversion of forest land.

. . .

There seem to be a few complications on this issue. For one the Saxena Committee has given very liberal and wide-ranging definitions of 'forest' and 'forest rights' as per its interpretation of the Forest Rights Act. It is another matter that the interpretation of statutes is a responsibility of the courts, not of a committee appointed by a minister!

The Saxena Committee, for example, defines 'forest' to include 'forest dwellers' as well as 'trees and wildlife', literally overturning the Apex Court's definition of 'forest' in the famous Godavarman case.

It also interprets communal and habitat rights of the primitive tribal groups to extend beyond their areas of residence to cover the entire eco-system.

Since the Forest Rights Act is a new piece of legislation these issues will need to be settled by the courts in due course of time, keeping in view the practicability of implementation.

In any case, the Orissa officials seem to have argued that they had complied with the legal requirements of the legislation (which, by the way, came long after the mining proposal was mooted) to the best of their ability.

Surely, Saxena and the MoEF cannot both be the prosecutor and the judge on this matter!

. . .

Also, what about development -- both of minerals, which are the nation's dormant resources, and the tribal groups, who inhabit the area?

From the Saxena Committee report (which is silent on this subject), it would appear that Mr Saxena would like them to continue as 'forest dwellers' in perpetuity so that they continue to enjoy their 'forest rights', living on roots and herbs and we continue showcasing their primitive tribal identity and abject poverty nationally and internationally!

Finally, what happens to the considerable investment that has gone into the industry?

Environmental and forest clearance procedures are about balancing the needs of development with those of conservation. To the extent possible the project proponents, including the state government, should be given an opportunity to correct the deficiencies. (After all it is the state government, not OMC/Sterlite-Vedanta, that has to settle the forest rights).

It is true that in extreme cases permission will have to be denied but that should have been before the start of the refinery when the required clearances were given.

To do so now will be unfair and damaging to the government's reputation for objectivity.

The author is Senior Fellow, Institute for Studies in Industrial Development, New Delhi.