One overriding fact will define the coming decade for India: the high probability that it will continue to achieve economic growth at an annual rate of 9 per cent, give or take a percentage point. That will compare with an average of about 7.5 per cent for the first decade of the new century, and about 6 per cent in the last decade of the 20th.

In grand, macro-economic terms, that does not sound like a seminal shift, for GDP will go up from Rs 60 lakh crore today (about $1.3 trillion) to 2.2 times that figure a decade from now.

India's GDP in 2020, at just under $3 trillion at today's prices and exchange rates, would be less than two-thirds of what China has already achieved in 2009: $4.6 trillion.

In global rankings, too, there will be relatively small shifts -- India will have become bigger than Russia and Brazil (two of the BRIC economies), and should also overtake Canada and Spain. It will therefore become the eighth largest economy in the world, as against the twelfth largest today.

And per capita income will have doubled to become a little better than where Sri Lanka's is today!

further. . .

These are substantial changes, but essentially incremental, and therefore none of them earthshaking.

India's share of global GDP, for instance, will be only slightly better than 4 per cent even in 2020 -- well short of the 24 per cent that prevailed more than three centuries ago, and not much better than the 3.8 per cent of 1952!

The more exciting story, therefore, will lie in the scale change that will become evident in specific markets. We have seen over the past decade how this works -- the number of new mobile phone connections has gone from 0.1 million per month in 1999 to 10 million now, an increase of a hundredfold. And total mobile connections have gone from less than 10 million to over 500 million.

What has happened in mobile phones will happen in many fields over the coming decade. Chiefly because the number of households with a monthly income of Rs 25,000 and more should more than treble, from about 30 million today to 100 million by 2020, with their average income becoming at least twice what it is today.

In other words, the spending power of the middle class will multiply six-fold. Depending on which way spending patterns move, some markets will grow tenfold in the next decade.

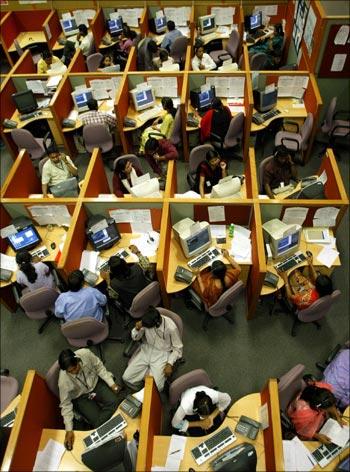

That kind of scale change will be the real story -- mimicking the software business, whose exports have grown from $5.7 billion 10 years ago to about $50 billion now. So when you pick the next crop of stars in the world of business, think carefully.

Airbus, for instance, has said that India's will be the fastest growing aviation market in the next 20 years (growing faster even than China's, which already has over 800 domestic planes, compared to about 200 in India).

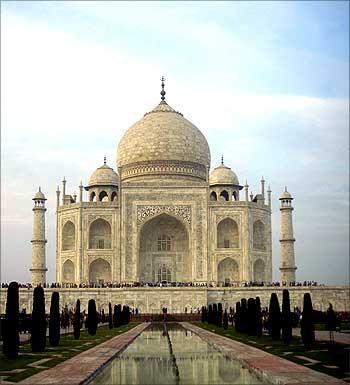

India will also be the fifth or sixth largest maker of, as well as market for, cars. And since India by the end of the coming decade will account for 10 to 12 per cent of world economic growth, the country will become a gigantic magnet (once again) for the world's companies that will come to do business.

It won't be a repeat of the East India Company story, but expect much greater internationalisation of the economy, especially if the ageing populations of Europe and Japan translate into little or no growth in what are today the centres of economic activity, driving their companies to look for growth elsewhere -- as is already happening.

The advent of scale change in India will create turmoil in global markets. If India's oil demand more than doubles over the next 10 years, and China's does the same, oil producers will have to deliver an extra 9 million barrels of oil per day to feed the extra demand from just these two countries.

Since the total increase in world oil production in the last three decades was barely 9 mbd, don't be surprised if oil prices catch fire at some point in the next few years.

It's going to be a disruptive decade ahead for other markets too: in metals, energy and even agro-commodities, as Indian demand starts looking more like what Chinese demand has been in the recent past.

If this explains why China has been busy in a one-country race to grab the world's resources, wherever they may be, perhaps it is time India took the natural resource game a little more seriously.

Domestically, the new game in town will be manufacturing. As the domestic market grows, domestic manufacture cannot be far behind. The problem, of course, is that in the age of climate change, this becomes highly problematic.

More immediately, expect bitter battles over land. The harsh fact is that India has 350 people per square kilometre -- something like eight or 10 times the global average. By the end of the decade, it could be 400 people per sq km.

Typically, then, if a large industrial project or power plant wants 5,000 hectares of land (or 50 sq km), it could displace as many as 20,000 people. Less, if the land is in an under-populated area, but still substantial.

Assume the setting up of dozens of such projects: in power alone, the country will need the equivalent of 40 ultra-mega projects of 4,000 mw each; in steel, domestic consumption could go up from 46 million tonnes today to perhaps 150 million tonnes.

To feed such demand and to make way for such projects, we are talking of displacing millions of people in the coming decade.

The question of whether this is feasible, and where the displaced people are to go, will be one of the prime issues of the decade -- especially in heavily populated states like West Bengal, where population density is thrice as high as the national average (over 1,000 people per sq km).

Nevertheless, expect sustained improvement in India's socio-economic indicators -- like a halving of the percentage of people below whichever poverty line you choose, a literacy rate by 2020 of 80 per cent (close to today's world average of 84 per cent), and life expectancy finally crossing the 70-year mark, perhaps even approaching 75 years.

All this will be achieved despite manifest deficiencies of governance, and the imperfect delivery of public health and education services by government agencies.

Perhaps because of these, India will continue to have only a 'medium' category score of about 0.7 on the human development index, short of the 0.8 that would categorise it as having a 'high' score. The index for India in 2007 was 0.61.

With many of these changes, and greater urbanisation -- more than a third of the people should be living in towns and cities in 2020 -- politics can be expected to undergo a change, for the better.

Citizens will be less concerned about voting their caste; instead, they will cast their vote for the politicians who they think are more likely to provide them with electricity, water, good public transport and clean air.

What can make this scenario come unstuck? Plenty, actually.

One can list the growing inequalities in the system -- of income, wealth and opportunity, the challenge of jihadi terrorism, the criminalisation of politics, the dramatic increase in the scale of political corruption, and the threat to the established order posed by the Maoists. These are obvious, because they are urgent issues even today.

An issue which has not received much attention comes from businessmen, because the bald truth is that India's capitalists have failed capitalism.

Take the business story that ran through the last year: the feud between the Ambani brothers over the supply and pricing of gas. The skeletons come tumbling out of the cupboard every time there is such a fight, and what comes out isn't a pretty sight.

No one also needs reminding that 2009 began with the breaking of the Satyam Computers scandal, the founder-chairman's arrest, and the company's collapse and its subsequent sale.

Other headline events during the year included the scandal over the handing out of telecom licences, with an inquiry by the Central Bureau of Investigation under way. There was also the Koda affair, with Rs 2,000 crore (Rs 20 billion) of unaccounted money being linked to the handing out of no fewer than 47 mining leases in a single day.

The headlines suggest the thesis that India's businessmen and politicians have come together to make hay from the push towards a market economy -- and thereby undermined the effort.

To be sure, businessmen have also shown that India's private sector works. There are Nano and Swach, the dramatic spread of telecom services, the greater efficiencies achieved through privatising Delhi's power supply, the steady flow of consumer goods of greater quality at reduced prices, the increased efficiency of companies like Maruti, the green initiatives of ITC. . .

But it is dangerous to turn a blind eye to the dark side, especially if the country seems to be undergoing a dangerous transition from the era of crony capitalists to the era of oligarchs -- businessmen who acquire and use political power for their own ends -- like the Reddy brothers who nearly toppled the Karnataka chief minister. Russia points to some of the dangers.

Boris Yeltsin launched a widespread privatisation programme in the mid-1990s, a variety of 'oligarchs' captured companies at throwaway prices, often used physical violence to intimidate, and developed political ambitions, before there was the inevitable backlash.

Boris Berezovsky bought an oil company and a TV station and funded political parties, but eventually had to seek asylum in Britain. Mikhail Khodorkovsky was another oil billionaire who developed political ambitions, only to lose his company and his freedom. Russia itself has swung back to authoritarianism.

The situation in India is not comparable, you would say and you might be right. Read on. . .

But Indian tycoons like the Reddy brothers now risk being tagged as robber barons -- a tag that links business success to political dealings, or to anti-competitive and/or unfair business practices.

It is worth finding out, for instance, which mining interests were behind the installation of Mr Koda as hapless Jharkhand's chief minister, and who arranged for the Congress party's support.

You could argue that all countries go through such phases -- the United States saw it in the late 19th century, just as Russia did a century later -- and that this is a stage through which India too is passing before market regulation, political oversight and the institutions of governance improve and become more effective.

That positive outcome is possible, of course, but has to be worked for and will not happen automatically. Indian democracy has withstood the test of poverty. It now has to demonstrate that it can withstand the test of growing prosperity.