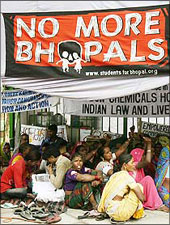

Next week's 'Recover your environment' workshop in Hyderabad is a tiny step towards compensating for how little has changed since the Bhopal tragedy, says Rajni Bakshi.

As the blame game over the Bhopal gas tragedy continues, with no meaningful justice in sight, it is natural to feel frightened and helpless. This is particularly true for people who live right next door to a hazardous or polluting industry.

As the blame game over the Bhopal gas tragedy continues, with no meaningful justice in sight, it is natural to feel frightened and helpless. This is particularly true for people who live right next door to a hazardous or polluting industry.

Demanding tighter regulation of hazardous industries, though vital, is not very comforting. What good are good rules if the government inspectors are corrupt -- looking the other way while a hazardous unit runs on faulty designs and/or bad maintenance?

Given the snail's pace at which both criminal cases and civil law suits proceed in India -- threat of prosecution is hardly a deterrent for the owners of hazardous industries.

Changing these realities requires such a high order of organisation and motivation that most people feel diffident about even attempting to be 'change agents'.

But here's a healthy antidote to both the fear and helplessness. A citizen's methodology that is tangibly constructive and doable -- even by those who are not full-time social activists.

From July 10 to 12, Cerana Foundation, a Hyderabad-based NGO, will host a 'Recover Your Environment' workshop, where citizens can find ways of protecting themselves from the dangers of toxic industries.

A series of such workshops is being organised in response to the deepening conflicts between the promoters of hazardous industries and the local communities, who are usually not adequately informed or consulted before the project is installed in their backyard.

A 'Recover Your Environment' workshop teaches participants how to assess for themselves whether a proposed project will be good or harmful for their environment, health, livelihoods, community resources, et cetera. People also learn how to monitor the hazards and related safety systems of an existing industrial unit.

The premise of such workshops is derived from the Indian Constitution. Article 51A(g) makes it the fundamental duty of every citizen to protect and improve the natural environment, including forests, lakes, rivers and wildlife, and to have compassion for living creatures.

For Sagar Dhara, the designer and organiser, these workshops are part of a broader shift that is now urgently needed. "If human society is to survive the environmental crisis it has created," says Dhara, "we must alter prevailing systems which provide gain-maximization for a few to new systems that will ensure risk-minimization for all."

Dhara, an environmental engineer, is building on the lessons of the Bhopal tragedy, which he sees as a multi-dimensional information failure.

Firstly, the information required to tackle an MIC (methyl isocynate) leak was never generated so there was neither event prediction nor an off-site emergency plan.

'Event prediction' (EP) refers to the process of identifying all possible risks posed by an industrial unit and accordingly preparing the vulnerable populations. 'An off-site event prediction' details the sequence of steps required to be taken in an emergency.

In the case of Bhopal, says Dhara, an off-site EP was neither asked for by the regulators nor prepared by Union Carbide. So even when the alarm was sounded people had no idea what it meant.

Secondly, life-saving information was not provided, such as properties of the hazardous substances being handled and what antidotes would work on those exposed to those toxins.

Dhara's research shows that the hazardous properties of Bhopal's killer gas, MIC, were known to Carbide but were neither asked for by regulating agencies nor voluntarily provided by Carbide to regulating agencies or the public. Had this information been made available, there would have been greater pressure on Carbide to prevent an MIC spill.

Thirdly, information on risk-mitigation action can play a critical role in saving lives. For example, hundreds of lives could have been saved if people living around the Union Carbide plant had known what to do in case of a gas leak.

Most people followed the natural instinct to run fast. This over-exerted their lungs and proved fatal for many. But no one had told them about the correct course of action was to cover the mouth and nose with a wet towel, because MIC is soluble in water, and then walk fast but not run in a direction perpendicular to the wind direction.

Since Union Carbide workers knew this they acted accordingly and not a single Carbide worker died.

Some regulatory agencies have, in principle, adopted these measures but implementation remains extremely poor. In the late 1990s, Dhara was a member of the Consent for Operations Committee of the Andhra Pradesh Pollution Control Board. This committee mandated that all hazardous facilities to put up notice boards with all information about the nature of hazards and what to do in the event of a catastrophic accident.

Most companies put up boards that stated their safety and environment policy but virtually none complied with the most important requirement -- a vulnerable zone map and a list of what to do in case of an accident.

To the dismay of Dhara and other citizen-activists, the Pollution Control Board was too weak-kneed to force companies to comply.

A National Disaster Management Agency was set up 20 years after the Bhopal accident -- and then with more of a focus on natural disasters than industrial hazards.

Next week's 'Recover your environment' workshop in Hyderabad is a tiny step towards compensating for how little has changed since the Bhopal tragedy.

Participants will learn tangible methods for using existing laws to demand information from hazardous industries and monitor the implementation of their safety procedures -- essentially doing what official watchdogs would do in a less corrupt and more efficient system. [Those wanting to learn more about this workshop can email: ceranafdn@rediffmail.com]

Dhara argues that every citizen is entitled to demand that hazardous facilities should cause zero risk -- to their lives, health, environment and livelihoods. Plus, every hazardous facility should furnish a bank guarantee, equal to the capital cost of the facility, which could be cashed if the zero risk clause is violated.

This approach is as much in the interests of business and industry as individual citizens. Businesses, like individual citizens, should demand more detailed information about and accountability from hazardous industries in their vicinity.

Instead, some business leaders are arguing in favour of limiting the liabilities of private nuclear power companies -- in order to attract investment in that sector.

But the same business leaders need to consider one basic question: Would they locate their own home or a unit of their enterprise next door to a nuclear power plant whose promoters can get away with denying the public crucial information about their operations and also have no fear of major civil or criminal liability?

Rajni Bakshi is a Mumbai-based freelance journalist and author of Bazaars, Conversations and Freedom: For A Market Culture Beyond Greed And Fear.